| Kaz | Enfo | Ayiti | Litérati | KAPES | Kont | Fowòm | Lyannaj | Pwèm | Plan |

| Accueil | Actualité | Haïti | Bibliographie | CAPES | Contes | Forum | Liens | Poèmes | Sommaire |

Le musée du Dodo

DODO AND SOLITAIRES, MYTHS AND REALITY

by

France Staub

Proceedings of the Royal Society of Arts and Sciences

avec tous nos remerciements et tout spécialement à Rosemay Ng.

"Should any copies of this work find their way to Mauritius or Bourbon, they may perhaps incite the lovers of knowledge in those islands to investigate further the subjec..." - Conclusion, Part I., The Dodo and its kindred, H.E. Strickland, 1848. |

FOREWORD

On the 13th of April 1995, an Exhibition was held in the Zoology Museum of the University of Amsterdam on the theme: The Dodo Raphus cucullatus, Didus ineptus.

Ben Van Wrissen, author of the Exhibition Catalogue, explained that its aim was to sift away the improbabilities and hearsay about Dodo knowledge, through an inventory of all known remains in Museums and a reappraisal of the sources.

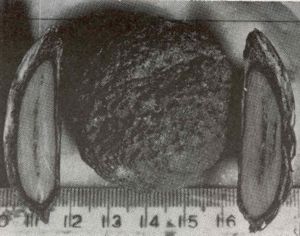

This endeavour was welcome to all those interested in dodology, as it was to the present author who was one of the signatories of the article entitled: "Did the Dodo do it?" in the Review Animal Kingdom (Cheke, et al, 1984). It was a refutation of S.A. Temple's postulate (1983) that the hard seed of an upland high-canopy tree, Calvaria major, now renamed Sideroxylon grandiflorum (Sapotaceae), could only germinate if triturated in a Dodo's gizzard, which usually contained a large rounded stone. A visit to the nurseries of the Mauritius Forestry Headquarters in Curepipe in 1977, had revealed dozens of beautifully-faring young Calvarias, sprouting in the most natural way, that dispelled the story (Pl. 1, 4). However, it went spreading around, being repeated to this day by many authors right down to the level of children's books.

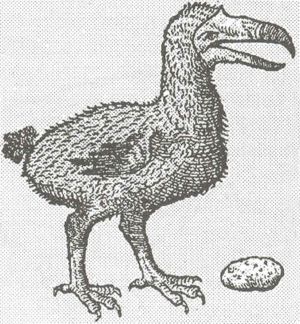

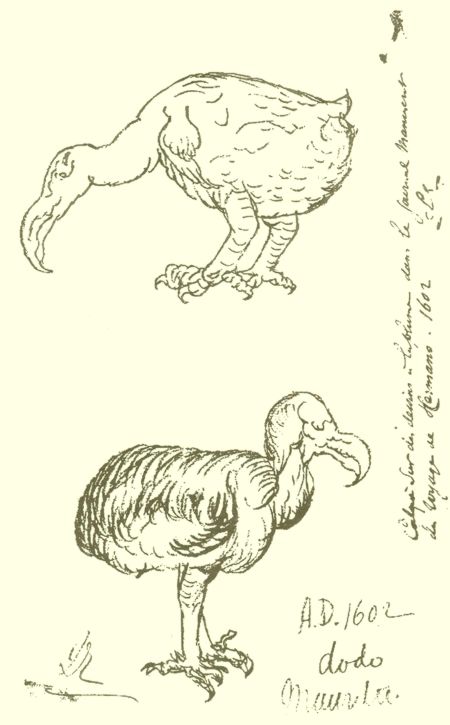

One of the more important revelations of the 1995 Exhibition was the discovery, during the preparation of a parallactic animation of the Dodo, that a correctly articulated skeleton, if projected into one of the classical images, presented a naturally more erect attitude than is commonly supposed. European painters like Savery and Van de Venne had probably depicted the newly arrived birds in their still ankylosed and crouched posture resulting from months of travelling in crates.

It should be pointed out that Andrew Kitchener, Curator of the Royal Museum of Scotland, had arrived at the same conclusion in 1993 through somewhat more intricate means: he had cut through Dodo bones to calculate weight stress on the femora and made plasticine life-size models to determine the volume of the bird by Archimedean displacement. He then determined its average weight as between 12.5 and 16.1 kg, a result which tallied well with the estimation of Van Wrissen of between 10 to 22 kg.

In his publications in the Archives of Natural History (a. 1993) and in the New Scientist (b.1993), Kitchener declares the Dodo to have been "a lithe and active bird", questioning Oudemans'postulate (1917) that the extreme fatness of the bird, as described by eye witnesses at certain periods, could be the result of seasonal orgies. "This, argues Kitchener, would have been an incredible feat for a large bird with a relatively low metabolic rate on a subtropical Indian Ocean island with limited seasonality."He also added that fatness could be accounted for in travelling birds by the biscuits and the weevils that went with them. It shall further be shown that Nature did provide weevils (p l.5 ,4) together with the rich oily food that quickly transformed Dodos into very fat birds at the onset of winter, to prepare them for the chores of reproduction. In the early summer of 1602, Reyer Corneliszoon, of the vessel Utrecht, had seen and described them in the off-season, when they had probably started thinning and moulting, noting that they "walked upright on their feet as though they were a human being."

For some years, I have been studying publications and data on the large apterous birds of the Mascarenes, acquiring, through numerous visits to the Archipelago in the company of botanists, a general knowledge of the indigenous vegetation. The climatic factors prevailing in the islands have not changed significantly since the 17th century, when these birds were still alive.

Apart from from the classical works on the Dodo, other interesting sources of information were the manuscripts of the Doyen Papers in the possession of the Mauritius Royal Society of Arts and Sciences. These are copies of the reports of the Dutch Captains that visited Mauritius after 1598, with a number of drawing tracings from the same. It was the work of M. Leopold Estourgies, who copied and translated them in French at La Haye Archives in 1873 and sent them to M. Charles Léon Doyen in Mauritius (Fig. 6). The latter had intended to write a History of Mauritius, but his early death prevented this. The manuscripts were made available to M. Albert Pitot who used them textually to write his now very rare book Teylandt' Mauritius (1905). This was fortunate as over the years, many documents were mislaid before the collection was put in the safe custody of the Society. Finally Ben Van Wrissen's well-documented Exhibition Catalogue (1995), graciously lent by Pierre Bourgault du Coudray, was of great help.

Information on the Rodrigues Solitaire is available from François Leguat de la Fougère's book (1708) and from Tafforet's Relation (Dupon, 1973).

Lougnon's Collected Reports of early visitors to Réunion (1970), especially those of Abbé Carré and Sieur Dubois, offer precious information.

It is hoped that this paper will bring some timely answers to the query set by Ben Van Wrissen in the conclusion to the 1995 Amsterdam Exhibition Catalogue on the Dodo: "There are still puzzles, white or not, fat or thin."

|

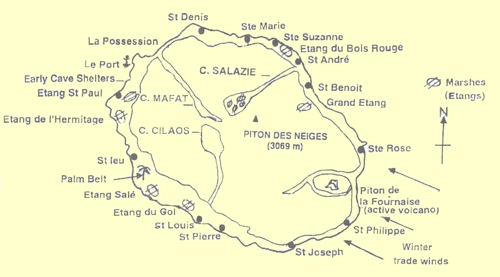

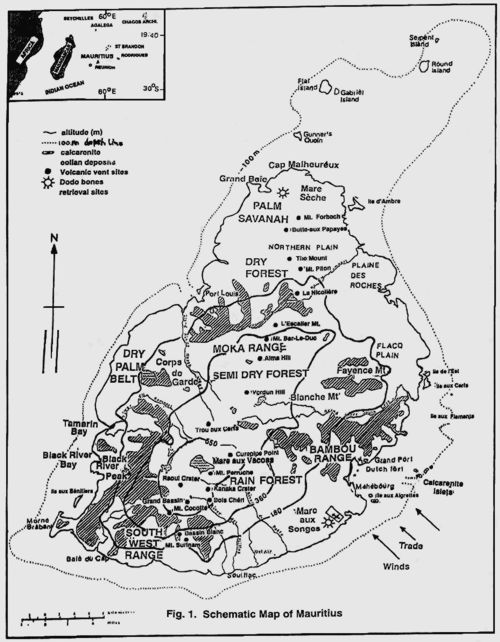

Fig. 1. Schematic map of Mauritius: In depicts the different micro-climates and vegetation types resulting from the position of mountain ranges across the flow of the moist winter trade winds. |

Fig. 2. Schematic map of pristine Réunion: The position of the more important marshes (Étangs), probably frequented by the Réunion Solitaire, an Ibis, is indicated. The Cirque de Salazie has four marshes named: Mare à Poule d'eau, Mare Citron, Mare à l'île Plate and Mare à Martin. A palm belt including Latania lontaroides extended along the west coast, topped by a semi-dry forest reaching up to 750 m, the abode of the Solitaire in Summer, as reported. The eastern and south-eastern slopes are covered in rain forest to sea-level. Cliquer ici pour agrandir la carte. |

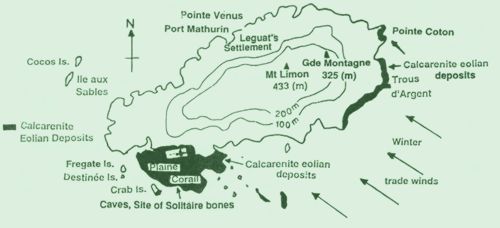

Fig. 3. Schematic map of pristine Rodrigues Island: Its low hills fostered a uniform climate and a vegetation of dry forest-type mixed with palm. Cliquer ici pour agrandir la carte. |

INTRODUCTION

Geography and volcanicity

The three volcanic islands of the Mascarene Archipelago are grouped on the Tropic of Capricorn in the south western Indian Ocean about 1'000 km east of Madagascar. Mauritius (Fig.1), in the central position, is 574 km from Rodrigues (Fig.3) to the east, with Réunion (Fig.1) at 280 km to west south west.

According to Montagioni and Nativel (1988), Mauritius, the oldest island, emerged from the sea at the southern tip of the Mascarene Plateau, at 20°10 S and 57°30 E. Its most ancient lavas are dated 7.8 million years. It grew to a high shield-volcano, 900 m high and 40 km wide, before collapsing and going through two other periods of activity and ultimately reaching quiescence 26'000 years ago. It now measures 1865 km2 and culminates to 828 m at Black River peak (Fig.1).

Réunion island emerged about 5 million years ago at 21°07 S and 55°32 E between the Mid-Indian Ocean Ridge and Madagascar, arising straight up from the ocean floor from a depth of 4'000 m. It measures 2'512 km2 and its active vol canicity has moved from Piton des Neiges, 3'069 m high, to Piton de la Fournaise in the South-east (Fig.2).

Rodrigues island, most recent of the three Mascarenes, rose from the sea 1.5 million years ago at 19°40 S and 63°25 E from volcanic activity at the meeting point of the African, Australian and Antarctic tectonic plates. It measures 109 km2, but according to Montagioni and Nativel (1988), it could have measured 1'200 km2 during the Last Glaciation when sea level was about 100 m lower. Alike Mauritius it is surrounded by a fringing reef, whilst Réunion has a reef and lagoon system along only 25 km of its west coast (Fig.3).

Colonisation of the Mascarene Islands by plants and birds

Cadet (1980) has aptly treated the subject revealing that the Mascarene Flora, for a large part, has an Afro-Malagasy origin.

Among the animals and plants that reached the three islands, some retained their original form, others evolved, giving rise to endemics. Cadet quotes Rivals (1952) about plant introduction when he mentions the role played by the prevailing winds for inter-island exchanges and more important, the carrying action of jet-streams and back-lashing cyclones coming from the west after traversing Madagascar.

At certain altitudes in the green forest belt that runs along the east of Madagascar, notably at Montagne d'Ambre, species associations exist identical with those found in the Mauritian rain-forests. However, the trees are about twice as large in girth and height as a result of the more favourable edaphic conditions.

The arrival of birds with seeds in their intestine occurred in the three Mascarene islands and started forestation from their dispersal. On his visit in 1606, Admiral Matelieff de Jonge explored Mauritius thoroughly and reported that it was covered with forests to the high peaks. He recorded palms and ebony to be dominant and mentioned the abundance of coconuts, meaning the dates of female Latan trees, Latania lodigesii, and Ficus fruits.

Palms will be discussed later. Twelve of the 450 ebony species in the genus Diospyros are endemic to the Mascarenes, ten occur in Mauritius and one in each sister island. Their dark green acorn-like fruit was probably a choice fruit for birds, including the Dodo and the Rodrigues Solitaire (PI. 6, 5). Ficus spp. (Moraceae) are common in the Mascarenes. Mauritius and Réunion share three endemic species: F. mauritiana (Pl. 6.3,4), F. laterifolia and F. diversifolia. The two other species F. reflexa and F. rubra occur in all three islands and also in Madagascar and the Seychelles, including Aldabra. They are most attractive to Parakeets and to Fruit Pigeons, specially those of the Treronidae from which the Dodo and the Rodrigues Solitaire are thought to have evolved.

When Europeans arrived in Réunion in the second half of the 17 th century, the island was totally forested except for an ericoid heath at high altitude. In the south eastern corner, lava flows from recurrent volcanic activity have maintained a barren area called the Burnt Spot (Fig.2).

Cadet mentions the role played in Réunion by large frugivorous birds like the Blue Bird, an apterous Porphyrio, for the dissemination of big seeds fallen to the ground. Parakeets and Pigeons also "fed on and dispersed other endemic plants, some with heavy fruits and seeds" for example:

- Sapotaceae : Sideroxylon, Mimusops (Pl. 6, 1 and 2), Labourdonnaisia

- Oleraceae : Olea, Linociera

- Rubiaceae : Myonima, Gaertnera

- Apocynaceae : Ochrosia, Tabernaemontana

- Lauraceae : Ocotea

- Flacourtiaceae : Scolopia

- Celastraceae : Elaeodendron

Referring again to Matelieff s summer visit to Mauritius in 1606, it may be noted that he was the first visitor to mention the presence of the Black Rat and the Macaque monkey, probable feeders on Dodo eggs. He enjoyed the flesh of fruit bats, dugongs and sea turtles but disliked that of the endemic tortoises and the Dodo, both lean at that period of the year. In his descriptions of the Dodo, the bird plumage was grey, its lean condition made its legs appear longer and its gizzard contained a stone as large as a fist (Fig.4). The Dodo, he thought, had ugly eyes and head.

The pristine beauty of Rodrigues island is well described by one of the first settlers, François Leguat, who sojourned there with a few companions from 1691 to 1693, to hide from religious persecution : "we could hard1y take our eyes off the mountains of which it almost entirely consists, they are so richly spread with great and tall trees: the valleys are covered with Palm trees, Plantains (Latania verschaffeltii (pl. 2, 1), Ebonies and several other sorts of trees."This was the habitat of the apterous Solitaire so weIl described by Leguat. It had probably evolved, like the Dodo, from an invading group of Treron Pigeons. Cheke (1987) gives 1761 as the probable date of its extinction. Two other birds, a Heron, Megaphoyx megacephala and a red-billed Rail, Erythromachus leguati, had lost the power of flight in such a peaceful and food-rich habitat. A starling, Necrospar rodericanus had adapted to feed nearly exclusively on tortoise meat and probably tortoise eggs. However, the Rat, probably introduced by early Arab or Portuguese navigators, had already infested the island and would soon exterminate the two endemic owls mentioned by Leguat, and the young Solitaires.

In Leguat's time about 46 endemic plants existed in Rodrigues, including a Pandanus and three endemic palms. These were also described by Tafforet, a visitor from Réunion in 1723: "Latan trees are met with all over the island, especially in protected areas and ravines. Together with the palm trees, they are dominant everywhere." They fruited profusely in winter (Pl. 2, 1) fattening the Solitaire, having induced it across the times, like the Dodo in Mauritius, to reproduce itself in that season. However from October to December, a drought usually occurs, preceding the January to May rainy spell that triggers flowering in the flora. At that period, crucial for the Solitaire and its young, many forest species then present took over the relay to produce fruit, right on to the full summer season, acknowledging Tafforet's mention: "the Solitaires live on seeds and fruits which they pick from the ground."

Following human settlement, Rodrigues had the good fortune to be visited by many naturalists and its gradual degradation has been recorded along and, finally, in Dr. Strahm's Red Data book published in 1989 which shows 94% of its endemic elements extinct or threatened. The endemic vertebrates are now represented by a Forest Warbler, Bebrornis rodericana, and a Yellow Fody, Foudia flavicans, both about fifty pairs in number and about five hundred Fruit-bats Pteropus rodericana.

Visits and reports of eye-witnesses of the Dodo in Pristine Mauritius

Date |

Season |

Vessels |

Journals |

19.9 - 2.10 |

Early Summer | Amsterdam

Friesland Utrecht Zeeland Gelderland |

Adm. Warwick's Fleet.

Data collected from the Second Book of Van Neck's Expedition 1601.

|

Descriptions of the Dodo (translations) "There are also a strange and grotesque specimen of a bird as large as a swan with a downy hood on the head, enormous and disgraceful, bearing a ridiculous bent bill. It had diminutive wings tipped with four grey feathers and a four-feathered curly black tail that stuck off its rounded rump. They were easily clubbed down but proved so rough, they had to be cooked for hours and got the name Walgvogels or Nauseating Birds, coming as second choice to the Pigeons". |

|||

Date |

Season |

Vessels |

Journals |

| 30.9 - 20.10 1601 |

Summer | Gelderland Guardian Utrecht Duyftken Zeeland |

Adm.Wolphaert

Harmanszoon's.

Fleet: Journals kept

at the Algemeen

Rijksarchief. Gelderland's Journal contains many pen drawings of the Walgsvogel. |

| Descriptions of the Dodo (translations) Fleet anchors at Morne Brabant. Boats brought back "Birds and dates". No water found.

Fleet moves to Port South East, Warwick Haven. Van Heemskerk in Gelderland's Journal 51: "The bird has a body like an ostrich, a great head and on the head a veil as if it was wearing a hood". Reyer Corneliszoon in Gelderland's Journal 62: "They walked upright on their feet as though they were a human being". "The bird was twice as big as a Penguin". The Journal mentions: "They often have stones in their stomachs as big as eggs. sometimes bigger". |

|||

Date |

Season |

Vessels |

Journals |

| Jan-end Aug 1602 |

Winter | Adm. Van Heems- Kirk's Fleet | Wilhem Van Westzanen's Journal: Voyage to the East Indies Amsterdam 1648. |

Descriptions of the Dodo (translations) Wilhem Van Westzanen was the first to call the Walgsvogel: Dodo or Dodaerse. On 25 July Captain Wan Westzanen and his sailors brought back to the Bruinvis very fat Dodos which tasted good to the crew. What remained was salted. On 4 August, 50 big Dodos were captured. Twenty five birds were so big and fat that two only were sufficient to feed the crew. The rest was salted. On another 3-day hunt inland, other crews of the fleet captured 20 more Dodos. (Translation: Rutgers Van de Loeff) |

|||

Date |

Season |

Vessels |

Journals |

| 1.1 - 27.1 1606 |

Summer |

Adm. Matelieff de

Zonge's Fleet: Orange Middleburgh Maurice Lion noir Lion blanc Le Grand Soleil Le Petit Soleil |

Matelieff

de Zonge's

Journal |

Descriptions of the Dodo (translations) Adm. Matelieff repeats Dodo descriptions already published in Van Neck' s Second Book adding that it usually had a stone as large as a fist in its stomach. His description of the vegetation of the island are most important and will be quoted further. He saw large number of rats and monkeys probable predators on Dodo's eggs and young. |

|||

Date |

Season |

Vessels |

Journals |

| 26.11-24.12 1607 |

Summer | Mm. Van der Hagen's. Fleet: Lion Noir Provinces Unies |

Van der Hagen |

Descriptions of the Dodo (translations) Adm. Van der Hagen meets Adm. Van Warwick at Port North-west (Port Louis) where he is repairing the Medemblick. Crews go camping two km south (actual estuary of River North-West). They live on Dodaerses, Pigeons, turtles and grey Parrots. There are few ebonies but plenty of cabbage palms. |

|||

Date |

Season |

Vessels |

Journals |

| 7.11-24.12 1611 |

Summer | Adm. Pieter Willemsz Verhoeven's; Fleet | Teylandt's Mauritius |

Descriptions of the Dodo (translations) In his reports, Adm. Verhoeven repeats the Second book's Accounts about Bird Population. He calls Dodos "Toterse" which were eaten by the crew together with Pigeons, turtle-doves and grey Parrots. They were caught by hand, but very carefully as they defended themselves by biting severely with their enormous bill. The colour of their small tail and wing feathers is given as aspen grey. Verhoeven had probably anchored at Port South-East. |

|||

Date |

Season |

Vessels |

Journals |

| 10.6-30.6 1627 |

Winter | William | Thomas Herbert's Relation of Some Years Travels in Africa and Asia, 1677 |

Descriptions of the Dodo (translations) From Teylandt's Mauritius - Translation: "Let us mention the Dodo whose body is big and round. His corpulence gives it a slow

and lazy walk. There are some nearing 50 pounds in weight. Its sight is of more interest than its taste and he looks melancholic as if he was sorry that Nature had given him such small wings for so big a body. Some have their head capped with a dark down, some had the top of their head bald and whitish as if it had been washed.They have a long and curved bill with the nostrils openings half way to the tip. It is greenish yellow. Their eyes are round and shiny and they have a fluffy plumage. Their tail looks like the sparsely beard of a Chinese made up of three or four short feathers. Their feet are thick and black and their toes powerful. They have a fiery stomach allowing them to digest stones like ostriches do". Herbert notices the abundance of Palms and Latan trees. |

|||

Date |

Season |

Vessels |

Journals |

| 1628-1634 | Peter Mundy's Travel Journal 1628-1634 | ||

Descriptions of the Dodo (translations) Paraphrase: The Dodos are twice as big as a Goose. They cannot fly nor swim, having cloven feet. A wonder they got to Mauritius, I saw two of them in Surat that were brought from thence. |

|||

Date |

Season |

Vessels |

Journals |

| 15.7-31.7 1638 |

Winter | St Alexis from Dieppe | François Cauche relation véritables et curieuses de l'Ile de Madagascar. |

Descriptions of the Dodo (translations) Translation: I have seen in Mauritius birds bigger than Swans, with no feathers, covered only with a black down. It has a rounded rump and as a tail, curly feathers which adjust in number to their age. In lieu of wings, they have similar feathers, black and recurved. They have no tongue and their large bill hangs downward. They are high on their legs which are scaly with three spurs to each foot. They call like a gosling. They are not as tasty as the Moorhens. They have only one egg as big as a penny bun and against it they put a white stone the size of a chicken egg. They lay their egg on a nest of grass in the forest. (Cauche indicates further that the Dodo's egg is as large as a Pink -Backed Pelican's egg (92.2 x 60.3 mm). If onekills a young, it is found with a grey stone in its gizzard. |

|||

Date |

Season |

Vessels |

Journals |

| Feb.-May 1662 |

Summer | Account of Volkert Evertszen | |

Descriptions of the Dodo (translations) Landing in Mauritius after the shipwreck of the Arnheim, Volkert Evertszen went hunting on small islets off the east coast probably at Ile aux Cerfs, Ilot Mangeni or Ile d'Ambre. He saw there birds larger than Geese but unable to fly. They had small wings "but were fast runners". |

|||

Date |

Season |

Vessels |

Journals |

| 1674 | Dutch Governor Hugo's Journal |

||

Descriptions of the Dodo (translations) A party sent to capture marooned slaves came back at Grand Port lodge with a young man named Simon. He had spent eleven years in the wild, from 1663 to 1674 and reported that during all these years, he had seen Dodos only twice. |

|||

Date |

Season |

Vessels |

Journals |

| 3.7.1681 | Berkley Castle |

Benjamin Harry's Journal (British Museum) |

|

Descriptions of the Dodo (translations) Chief-Mate Harry reported that :"first of winged and feathered fowls, the less passant are Dodos whose flesh is very hard." This was the last mention of the birds. |

|||

The Dodo and its summer time diet

From the above accounts of the Dodo, two different portraits of the bird emerge: the summer-time Dodo (Fig. 4) met by the crew of Vice-Admiral Van Warwick in 1598, so lean, hard-fleshed and "tough even after hours of cooking" that it was branded Walgvogel or Nauseating bird, and the winter-time Dodo (Fig. 5), seen in June 1627, July 1658, and August 1602 respectively by Thomas Herbert, François Cauche and Captain Wilhem Van Westzanen, who all describe its fatness, the latter naming it Dodaerse or Big behind, which altered to Dodo and so was to remain.

A closer look at the above list of eye witnesses reveals that all those who mentioned the Walgvogel visited Mauritius in early summer, from September to December, about the time the bird had just finished its reproductive chores and was starting to moult as discovered by Hachisuka (1953), when he studied the early Dutch drawings. Quite naturally those visitors declared their preference for the tastier perching birds: doves, pigeons and parakeets that were then at the peak of their form and about to breed.

Around October, the dates of Palms and Latans cease to drop and forest trees would then take the food relay by throwing down their first ripe fruits, luring away the Dodo and its young to the woody inland plateaux. However, this manna from the forest canopy would gradually come to an end at the turn of January whilst dark rain clouds started to waft in more and more from the sea, triggering the flowering season.

Admiral Matelieff is the best chronicler of the summer-time Dodo and its environment, as he spent the whole month of January 1606 in Mauritius. After reporting the Dodo to be in its gaunt Walgvogel stage as did Van Neck, he gives an inkling of the impending harsher conditions by recording that the forest trees he saw climbing up to mountain tops were now fruitless. He noticed large numbers of ebony trees and palms and pointed out that the female latans which he mistook for coconut trees, were starting to fruit, together with the ubiquitous Fig trees, probably the conspicuous red-fruited Ficus mauritiana (Pl. 6, 3 and 4). These fruits, however, would only mature and drop with the onset of winter, four months later.

Whilst its winged cousins, the Pink Pigeon (Nasoenas mayeri) and the Dutch Pigeon (Alectroenas nitidissima) were bridging the food deficiency by feeding on young leaves and flowers, the Dodo's only recourse would have been to survive by eating root bulbs, young shoots and perhaps fallen leaves, like the Rodrigues Solitaire. As remarked by Admiral Matelieff, it had developed strong legs and claws, probably to survive the lean days by scratching away at litter and pebbles after molluscs and insects.

The Dodo and its winter-time diet

It may be postulated that this fasting period created a strong hunger-complex in the Dodo and it fell greedily on the proffered manna that started to rain down from the palm trees at the turn of March. This probably attracted it back to the littoral Palm-belt that girded the western board, and to the north of Mauritius, when it started to indulge in those "orgies" which Oudemans (1917) and Kitchener found hard to imagine. In these sheltered regions it also found protection from the cool moist trade winds that induced development of a lighter fluffy plumage more adequate to the milder micro-climate, as noted by Herbert and other visitors.

Three eye-witnesses gave similar descriptions of the over-fat winter Dodo (Fig. 5), covering the whole season: Thomas Herbert arrived in June 1627, François Cauche in July 1638 and Wilhem van Westzanen during winter in 1602.

From Herbert's record of the Dodo in June, one can pinpoint the following traits: "his body is big and round, his corpulence gives him a slow and lazy walk. There are some nearing 50 pounds". The following remark is to be noted: "some birds have their head capped with a dark down (probably males), some have the top of their head bald and whitish" (probably females). One can deduce that the Dodos were already mating in June and that the scars left on the crowns of the females by the mounting males ensued from securing a hold. He remarked their powerful claws and a "fiery stomach allowing them to digest stones like ostriches do". He mentioned the abundance of Palms and Latan trees which at the time fruited profusely .

The fat oily flesh of the Dodo was overpowering to Herbert: "greasie stomach may seek after them, but to the delicate they are offensive and of no nourishment". Admiral Matelieff had preferred the taste of their thick gizzard muscles. De Bondt, quoted by Hachisuka preferred the breast muscles which, though fat, were eatable and the flesh so abundant that"three or four Drontes were sometimes sufficient to feed a hundred seamen".

François Cauche landing in Mauritius on the 15th of July, added new features to the Dodo in winter-time: "it is bigger than a swan and covered in a black down". This was confirmed in portraits of the live bird imported to Europe, by Roelandt Savery. Cauche mentioned that the Dodo's fat was a good cure for aching muscles and nerves and its call to sound "like that of a gosling". His remark about the Dodo "standing high on its legs" indicates an erect posture, as rediscovered by Kitchener and Van Wrissen, even in winter time when it was fat.

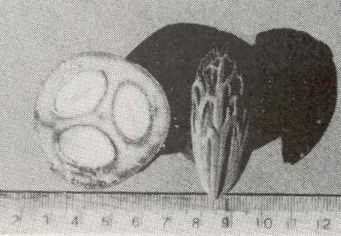

Cauche was the only visitor who witnessed the Dodo at its nest: "the female lays one white egg the size of a penny bun in a nest of grass which she gathers in the forest."As he described elsewhere a penny bun to be the size of the perching pink-backed pelican's egg, Pelecanus rufescens, it would therefore have measured about 92.2 x 60.3 mm, according to G.L. Maclean's edition of Robert's Birds of Southern Africa (1985). Cauche's observation that the Dodo placed a stone as large as a hen's egg in the nest seems to indicate a defence reflex against predation, a confusion device still practised in the. Cargados Carajos islands by nesting Brown Noddies against marauding Frigate birds (Staub and Guého, 1968). Cauche also mentioned a grey stone always found in the young Dodo's gizzard when it was killed. Curiously enough this was observed to be also the case with the young Solitaire in Rodrigues by François Leguat. Stony Palm and Latan seeds had to be ground to expose the softer embedded kernel to the action of gastric juices.

In the month of August, Wilhem Van Westzanen probably saw some Dodos in their brooding activities, which made their capture easy but added to their reputation of being stupid. However, as in the case of the Solitaire in Rodrigues, the crews soon learnt that they could aptly defend their territories by biting viciously. On 25 July 1602, very fat birds had been brought on board Captain Westzanen's vessel, the Bruinvis; on 4 August, 24 or 25 birds were again collected "so big and so fat that two only were sufficient to feed the crew, the rest being salted". In 1607, Admiral Van der Hagen declared salted Dodos "quite palatable". This must have increased interest in their capture by the victualling ships.

The Dodo population of pristine Mauritius must have been kept at a fairly constant level by the culling of cyclones. Thickness of the woods, boulder-strewn valleys, numerous caves and deep lava tunnels, offered a certain protection and survival against the directional persistence of cyclonic winds. Bellanger, visiting Réunion in 1771, was told by the inhabitants that a day or two preceding a cyclone, birds, tortoises and other animals usually retired to rocky nooks and caves till the winds abated. In Rodrigues it was in the south-western calcarenite caves that relicts of the extinct primitive avifauna were found (Fig. 3), the birds having been probably drowned or trapped in their shelter by the sudden flooding of subterranean streams. In the sixties, I witnessed the havoc caused to endemic birds by perhaps the severest cyclones of the century Mauritius had to face, namely Alix, Carol, Beryl and Jenny, with winds approaching 200 km per hour, resulting in alarming numbers of carcasses of endemic birds, with conspicuous Pink Pigeons, strewn in the mud on the forest floor (Staub, 1971).

Human settlement with its influence on game, added to the sequelae of predating domestic animals turned feral, were probably the main reasons for the disappearance of the Dodo and the Rodrigues Solitaire. Forty-three years only after the arrival of Gooyer, the first Dutch governor, and his party in Mauritius in May 1638, a visitor, Benjamin Harry, Chief Mate of the Berkley Castle, wrote the last record of the bird in his Journal now kept at the British Museum: "first of winged and feathered fowls, the less passant are Dodos whose flesh is very hard."

Seven years before, a runaway slave retrieved from the woods by Governor Hugo after eleven years in the wild had revealed he had seen the Dodo only twice. In 1693, Leguat, traversing the island from the North-West, right across to reach the Dutch fort at Port South-East, did not see any. Lack of energy-rich Palm fruits cannot be evoked, as Governor Lamotius, in response to a query by his Superior Simon Van der Stel at the Cape, had revealed ten places where they were still abundant in 1690 (Pitot, 1905). The interest had been aroused by Lamotius' proposition to start a regular industry in arack production from Palm sap distillation. He had already made contracts with some local farmers in which it was stipulated that each tree felled when spent should be replaced by planting a new one (Pitot, 1905).

Distribution and food value of the Mascarene Palmae and Pandanae

|

Latania lontaroides, Red latan, Réunion. Photo F.P. |

It is of interest to consider the distribution and extent of the palm Savannah in 17th century Mauritius. Vaughan and Wiehé (1937-1941) stated in their Studies of the Vegetation of Mauritius that: "the Dutch also record a type of vegetation occurring in the coastal plains, particularly in the North and west, whence palms were frequent and where they could graze their domestic animals. This community was probably a Palm Savannah similar to the type still to be found at Gunner's Quoin. The crown shaft was edible, the leaves and stem were used for thatching and building and alcoholic liquors were made from the sap. In consequence they rapidly became extinct, and no trace of this community now exists on the main-land". (Fig.1).

The Palm trees of the Mascarene Archipelago belong to the Borassoidae and the Arecoidae (Moore and Guého 1984).

The Borassoidae in the genus Latania have evolved three species, one in each island. With their profuse bunches of large fruits, they were probably the main fattening agents of the Dodo and the Rodrigues Solitaire. Leguat had noted that "having better things to eat, we left the dates of the Plantains (Latans) for the turtles and other birds to feed on, particularly the Solitaires."The Blue Latan Latania lodigesii occurs in Mauritius, the Yellow one, L. verschaffeltii in Rodrigues and the Red one, L. lontaroides in Réunion. The latter could have been the species concerned in the case of parakeets, mentioned by Feuilley (Barré and Barau, 1982): "they are very good to eat, especially when they are fat, which is from June to September (Winter) because in those months, certain trees throw down a sort of wild seed these birds feed on."

|

Dictyosperma album, White palm. Photo F.P. |

The Arecoidae present four genera: Acanthophoenix, Dictyosperma, Hyophorbe and Tectifiala, all with small fruits - In Mauritius, Tectifiala offers one species, T. ferox and Hyophorbe five species, of which H. vaughanii and H. amaricaulis have evolved in the wet and windy highlands at an altitude above 500 m, a site probably shunned by the Dodo with its light plumage at their winter fruiting time. Hyophorbe lagenicaulis or Round Island Bottle Palm, probably evolved on the islet after the isolation of the rising seas of the Holocene. The Palm's unusual bottle shape in the younger trees would have surely triggered comments from the early visitors had they occurred on mainland Mauritius. The two remaining Hyophorbe Palms : H. verschaffeltii in Rodrigues and H. indica in Réunion Island are reputed to have poisonous fruits, the second one occurring between the altitudes of 175 and 600 m. Dictyosperma has two species: D. album, probably the dominant tree in the Palm Savannah of pristine Mauritius, now cultivated, and D. album var aureum, dominant in Rodrigues at Leguat's time, actually on the verge of extinction. An aberrant sub-species occurs on Round Island. Last-named of the Mascarene Palms, but the richest in palm oil, Acanthophoenix rubra occurs in Mauritius and Réunion. In the latter island, it grows from sea level to 1350 m and, in Mauritius, it is now rare in the forest at all altitudes.

|

Latania lodigesii, Blue latan. Photo F.P. |

A spiky palm tree, illustrated by François Leguat, with bunches of dates and one of his companions perched in the tree tapping sap, has probably disappeared from Rodrigues, through selective culling (Strahm, 1989).

The Pandanae are well represented in the cool upper wetlands of Mauritius with twenty species. Pandanus vandermeerschii formed part of the coastal belt flora. Its fibrous drupe was probably no match for the stout-beaked and stone-armed gizzard of the Dodo (Pl. 4, la, b). Relicts of this species are still extant at Round island and on a spot in the cliffs of Souillac (Pl. 4, 2).

Common at the time of Leguat's visit in Rodrigues, Pandanus heterocarpus is still widespread in the island and its fruit has been used as food in time of drought. Dropping its ripe drupes from March to December, it could have been an item in the Solitaire's diet.

In Réunion, three endemic species occur at higher altitudes: Pandanus montanus, P. purpureus and P. elegans. Cadet is uncertain about their propagator, but the bright red drupes of P. montanus seem to indicate an avian agent. These three Réunion species have been omitted in Table 1. However, the other Réunion palms have been listed, for they could have been concerned by the observations made in 1704 by an early visitor, Feuilley (Barré and Barau, 1982) as already mentioned. It was thought that a better appreciation of the fattening food value of the fallen fruits from the Mascarene Palms and Pandanae could be obtained from an estimation of their protein and fat contents.

|

Hyophorbe indica, Poison palm. Photo F.P. |

Dr. Christine Halais has kindly agreed to study the nutritive values of the Palm and Pandanae fruits of the Mascarene islands and is of opinion that the extreme fatness of the Dodo and the Solitaire could well have been attained by feeding on the fallen ripe dates of these plants during the three to four months preceding their reproduction, as revealed by the texts on poultry nutrition. According to these texts, Palm kernel meal, which is a recognized feed, has the following proximate composition: Dry matter: 10%, Crude protein: 19% and fat (ether extract): 2%.

With respect to poultry, the Metabolizable Energy content of Palm kernel meal is 1610 kcal. per kg (6.7 MG per kg)1.

The quantity of Metabolizable Energy (M.E.kcal.) required for weight gain in poultry is as follows:

Weight of pullets (kg) M.E. cal/kg weight gain |

1.628 6956 |

|

2.218 77892 |

Calculating from the above data, 4.8 kg of Palm kernel meal is required to increase the weight of a pullet from 2.2 kg to 3.2 kg.

As already mentioned, notable additions to the Dodo's diet were the insects which invariably invade the fallen fruits of the Blue Latan, L. lodigesii, a few hours after they have dropped to the ground (Pl. 5 ,4). Dr John Williams identified some insects encountered in them:

- Rove beetles (Staphylinidae, Coleoptera)

- Nitidulid beetles (Nitidulidae, Coleoptera), frequent Earwigs (Dermaptera)

- Ants (probably Pheidole sp.)

|

Hyophorbe lagenicaulis, Bottle palm. Photo F.P. |

Table la.

Total protein and total fat available in the endemic Mascarene palm fruits to:

the Dodo in Mauritius

% dry matter |

% total protein |

% total fat ether extract |

||||

Pulp |

Seed |

Pulp |

Seed |

Pulp |

Seed |

|

Dictyosperma album, White palm |

39.60 |

84.60 |

1.10 |

3.60 |

0.01 |

0.60 |

| Hyophorbe lagenicaulis, Bottle palm | 11.30 |

64.60 |

1.37 |

3.60 |

0.60 |

0.60 |

| Acanthophoenix rubra, Red palm | 40.10 |

79.40 |

2.50 |

3.50 |

5.60 |

1.90 |

| Latania lodigesii, Blue latan | 31.70 |

60.60 |

1.51 |

3.30 |

0.35 |

0.24 |

| Pandanus vandermeerschii, Pandanus drupe | 43.50 |

2.10 |

0.32 |

|||

the Solitaire in Rodrigues

% dry matter |

% total protein |

% total fat ether extract |

||||

Pulp |

Seed |

Pulp |

Seed |

Pulp |

Seed |

|

Dictyosperma album, var. aureum, |

39.50 |

29.60 |

1.30 |

1.00 |

0.24 |

0.13 |

| Hyophorbe verschaffeltii, Poison palm | 54.10 | 2.10 |

3.80 |

0.12 |

0.50 |

|

| Latania verschaffeltii, Yellow latan | 25.70 | 51.50 |

1.04 |

2.57 |

0.43 |

0.12 |

| Pandanus verschaffeltii, Pandanus drupe | 23.80 | 5.90 |

0.62 |

|||

the avifauna in Réunion

% dry matter |

% total protein |

% total fat ether extract |

||||

Pulp |

Seed |

Pulp |

Seed |

Pulp |

Seed |

|

Dictyosperma album, White palm |

39.60 |

84.60 |

1.10 |

3.60 |

0.01 |

0.60 |

| Acanthophoenix rubra, Red palm | 40.10 | 79.40 |

2.50 |

3.50 |

5.60 |

1.90 |

| Hyophorbe indica, Poison palm | 15.60 | 20.30 |

1.10 |

1.30 |

0.31 |

0.06 |

| Latania lontaroides, Red latan | 27.10 | 51.0 |

1.50 |

3.40 |

0.20 |

0.27 |

Table lb.

Total protein and total fat available to the Dodo in some Mauritian forest fruits :

|

% dry matter |

% total protein |

% total fat ether extract |

|

Diospyros egrettarum, Ebony |

66.60 | 1.40 |

0.02 |

| Diospyros revaughnii, Ebony | 63.50 | 2.60 |

2.40 |

| Ficus mauritiana, Fig | 14.80 | 1.50 |

0.25 |

| Elaeodendron orientale | 69.00 | 2.20 |

0.90 |

| Antidesma madagascariensis | 52.00 | 2.50 |

2.60 |

As revealed in these tables, Palm fruits appear generally richer in protein than forest fruits and outstandingly so in fat in the Red Palm, Acanthophoenix rubra, probably the commonest of the species then found at all altitudes in Mauritius and Réunion.

To conclude this exposé and the first part of Ben Van Wrissen's puzzle, it could be presumed that the Dodo was inordinately fat and also inordinately thin, at different seasons.

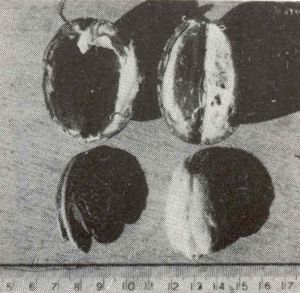

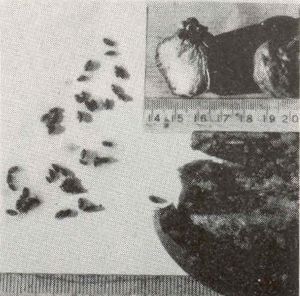

Digestible parts of the Latan and Palm dates |

|

|

|

Latania lodigesii date. Seed cut open sagittaly to show tegument and kernel, and a basaltic stone (90g), probably from Dodo's gizzard, collected at La Mare aux Songes by Pierre Bourgault du Coudray. |

Latania lodigesii, date sectioned to show arrangement |

|

|

Latania verschaffeltii date parts proffered tho the Rodrigues solitaire. |

Load of insects from a fallen L. lodigesii date. Typical palm date of Hyophorbe vaughanii, grazed show fibrous pulp and kernel (inset) |

Origin and affinities of the Mauritian Dodo and Rodrigues Solitaire

Julien Desjardins, a founder member of the Mauritius Royal Society of Arts and Sciences, made a thorough research of fossil bones in the Flacq District where he lived, and found only incomplete fragments of the osseous cover and humerus bones of endemic tortoises. At Plaine des Roches and at Montagne Blanche, they were scattered on the ground. At Mare La Chaux and Riche Mare, they occurred in heaps, buried in mud at a certain depth, and covered by stagnant water.

It was therefore with great interest that, at an Anniversary Meeting of the Society on the 13th of April 1866, under the Presidency of its Patron, Sir Henry Barkly, Governor of Mauritius, that the assembled members learned from the Report of the Secretary, Mr. Louis Bouton, that George Clark had discovered in the preceding year, at La Mare aux Songes near Grand Port (Pl. 1, 3), the bones of Flamingoes and Drontes, together with Tortoise bones, some with nearly entire shells. "We are now aware that the specimens subsequently presented by Mr. Clark to the British Museum consist of the almost complete skeleton of the bird (Dodo)... At all events the vexed question, so long under discussion, for want of sufficient evidence, of the classification of the Dodo in the natural order of Birds, is therefore now set at rest. Professor Owen is of opinion that it belongs to the natural order : Rasores, family: Columbideae."

A second prospection at La Mare aux Songes by Théodore Sauzier in 1889 had procured not only a large number of Dodo bones, but also remains of many other extinct birds which confirmed the descriptions of Captain Willem Van Westzanen on his 1602 visit. A distribution of the finds to many foreign museums ensued and a few Dodo skeletons mounted.

Another site which probably conceals fossil bones is Mare Sèche, about two km east of Grand Baie, an area which is water-logged all the year round (Fig.1). In June 1973, Mr. David Ball had dug there a core hole 75 m deep, later sealed with the mark C.W.A./G.W.R 315. Compressed air forced down the hole had brought up bones of Testudo triserrata and a cervical bone of the Dodo.

According to the core analysis, the bones must have laid in the 3 m deep topmost layer of green to brown clays, permeated by the phreatic water-table rising through porous vesiculated layers of lava flows from the Forbach volcano (Fig. 1), which built up this part of the northern plain 100'000 - 25'000 Bp. (Saddul 1995).

The Mauritius Royal Society of Arts and Sciences, approached at the time, could not obtain legal rights for prospection, in which the author had volunteered to help.

In 1841, Professor J.T. Reinhardt, after examining a Dodo skull he had discovered in the Zoology Museum of Copenhagen, had mentioned for the first time that the bird could have evolved from a giant Pigeon.

In 1848, Strickland and Melville revealed for the first time that bones of the Rodrigues Solitaire, encrusted with deposits, had been discovered by a resident, Mr. Labistour, in caves at Plaine Corail in 1789 and sent to Cuvier for identification. After a quick visit to Rodrigues during his term of office in Mauritius, Edward Newton sent over a party to explore the caves in 1866. Two thousand Solitaire bones were retrieved. Together with his brother Alfred, Professor at Cambridge University, he presented a remarkable paper on the bird at the Royal Society of London in June 1868.

Dr. Melville in the osteological part of the famous monograph "The Dodo and its kindred", published in 1848, had concluded: "We have now ascertained that the cranium of the Solitaire resembles that of the Dodo in numerous important points, differing in such respects only as would justify us in regarding these birds as specifically distinct... The marked dissimilarity in external form between the Dodo and the Solitaire and the position of the caruncular ridge in the latter, together with the shorter beak, fully justify the establishment of another genus Pezophaps in the Didinae, to include the lost form. That the Dodo and Solitaire belong to the same extinct sub-family of the Columbidae, characterized by the peculiar structure of the cranium and rudimentary wings, no one will, we trust doubt, who has carefully and impartially examined the evidence... We regard the Dodo and its affine the Solitaire, as territorial flightless modification of the treronine sub-type, but with no immediate affinity with the ground Pigeons as Goura, Caloenas, etc. which are more directly allied to the ordinary Columbines."

Recent important research on the Dodo was triggered by the discovery of a Dodo skeleton in the Mineralogy-Geology Museum of Delft, examined by Tim G. Brom and Tincke G. Prins (1988), who concluded that : "neither the traditional osteological studies nor our recent microscopic investigation of feather remains have yielded synamorphies for the Dodo and the Columbidae... It is therefore of great importance that all the remains of the Dodo that still exist be documented in Dodo literature."

The remains of the "Oxford Dodo ", a fabulous relict, is in the custody of the Ashmolean Museum. In 1755, the stuffed Dodo that was exhibited looked so degraded that it was junked for burning. The timely arrival of a new curator, Mr. Huddersfield, saved the head and foot.

Brom and Prins (1989) published their study of the feather remains from the head of the Oxford Dodo in the Journal of Zoology, London. Their conclusion expresses the latest opinion on Dodo affinities: "our findings, though derived from limited material, suggest that the Dodo resembles pigeons more than rails. We follow Cracraft (1981) in retaining the Dodo in the family Columbidae".

Aberrant forms of the Columbidae culminating in the Dodo type

The Columbidae comprises 48 genera and 284 species. Man has exploited this tendency to diversify to obtain new domestic races whilst Nature has fostered a number of aberrant forms especially in the large 36 Imperial Pigeons, some of which are here mentioned.

It is to be noted that many of these Pigeons were attracted to the oil-rich dates of Palm trees whenever they occurred in their habitats, resulting in extra fattening, over-hunting and eventual threat of extinction. So it happened with the Top-knot Pigeon of Australia and the Bangalow Pigeon Palm, and with the New Zealand Pigeon and the Nikau Palm. The latter bird was preserved in its own fat by the Maoris to be eaten during festivities. Costa Rica is also host to the large Scale Pigeon that feeds on the Moral Palm and Figs. The 38 cm long Pheasant Pigeon of New Guinea has short wings, long legs and lives on the forest floor. It flies very short distances when disturbed. Finally the Tooth-Billed Pigeon of Samoa, Didunculus strigirostris, evolved a Dodo-like bill, equipped with three projections on each side of the lower bill. It feeds on dropped fruits on the forest floor, which it presses down with its feet whilst tearing at them, parrot-wise, as probably did the Dodo, with Pandanus and Latan dates. The three Crowned Pigeons of New Guinea, largest in the Columbidae are Imperials that can reach 73 cm in length. Ground feeders they are thought to add insects and molluscs to their diet. So could have done the Dodo in droughty season.

The Treron fruit-eating Green Pigeon numbers 21 species and is also found in Asia. Treron calva, the African Green Pigeon, a greedy feeder on Figs, is most common on the African continent. Treron Pigeon radiated to Madagascar and the Comoros as Treron australis reaching the Mascarene archipelago where it is thought to have evolved into the Dodo in Mauritius and the Solitaire in Rodrigues.

The regular availability of high-energy Palm fruits may have induced in the Dodo an overtolerance which, through eons of time and in the absence of enemies, increased the body weight beyond lifting capacity. Gradual reduction of the wings followed, till the bird was permanently grounded. To quote Strickland (1848): "after flying to Mauritius such a bird might wander from tree to tree, tearing with its powerful beak the fruits that strewed the ground, and digesting their strong kernels with its powerful gizzard... such in my opinion was the Dodo a colossal, brevipennate, frugivorous Pigeon."

It was probably for the same reason, taking into account the genetic trait of the family, that the Rodrigues Solitaire developed also into a large brevipennate bird.

The answer to the other part of Van Wrissen's query about the colour of the Dodo's plumage: White or not ? seems to be resolved by default on the discovery that the Réunion Solitaire was in fact an Ibis which could well fit the description of the early travellers. Tatton and Bontekoe's mention of white birds could probably apply to its juvenile form, as described later.

Reference to the list of the reports of the eye-witnesses given above shows that they all agree about the grey colour of the Dodo plumage with lighter-coloured wings. "Grey" is the name of a neutral tint that usually applies, even when it warms to shades of brown or cools up to blues or greens.

Sir Hamon de l'Estrange, who had seen a live Dodo in a London shop in 1638, reported "it was coloured before like the breast of a young cock fesan, and in the back of dunn or dearc colour". This suggests different shades of greyish brown which could apply to the plumage of the Dodo depicted from a live specimen by Roelandt Savery in his picture The Fall of Adam, dated 1626, which was formerly exhibited in the Royal Gallery of Berlin, of which a freshly restored copy is now hanging on the walls of the Mauritius Institute of Port Louis.

Perhaps the finest Dodo portrait from a live bird by Roelandt Savery which I used to admire in South Kensington National History Museum in London in my student days, is in brown golden shades, with whitish wings and tail. A copy by Keuleman done in 1872 for George Edwardes is now in the Hachisuka collection in Tokyo, and its reproduction decorates the first page of Professor Hachisuka 's book "The Dodo and kindred Birds".

The Rodrigues Solitaire, Pezophaps solitaria (Gmelin 1788)

The Rodrigues Solitaire, like the Dodo, evolved probably from a Treron Fruit Pigeon which reached the Mascarenes from Madagascar or Africa. François Leguat who had feasted on it during his sojourn of three years in Rodrigues (1691-1693) gave a good drawing of the bird in his Relation published in Amsterdam in 1708, in which it looks as stout as the Dodo. According to Naval Officer Tafforet, another trustworthy witness, it weighed 20 to 25 kg. Tafforet had been sent to Rodrigues by the French authorities of Réunion to report on the resources of the island. He eventually spent nine months there with a party. His report was discovered by chance in the Archives of the Ministry for Marine Affairs in Paris in 1874 by John Rouillard and subsequently published by Milne-Edwards. It was again published by Dupon in 1973.

To quote Leguat: "from March to September (winter months), Solitaires are extraordinarily fat and their taste is excellent, especially the young." We have already mentioned that it relished feeding on Latan fruits (L. verschaffeltii). As mentioned before, Tafforet completed the diet by observing that the bird survived the fruitless period of December "by living on seeds and leaves they picked from the ground."

A French astronomer, Abbé Gui Pingré (1763) who visited Rodrigues in 1761 to observe the transit of Venus, reported the bird to be near extinction. He had been told by the Commander, Mr Marlène de Puvigné, that it was found only in remote corners of the island. This statement was the last mention of the bird.

In 1786, the bones of the Rodrigues Solitaire were discovered in some deep calcarenite caves at the western tip of the island and described by Strickland and Melville in 1849. H.H. Slater, member of a British Expedition to Rodrigues in 1874 to observe another Transit of Venus, gathered many more bones from the caves, including complete skeletons with a gizzard stone in the middle of the rib cage. Leguat had mentioned that it was usually found not only in adults, but also in the stomach of the young, and that he used to keep one to hone his knife with.

It is not easy to understand how Geoffrey Atkinson, a lecturer in Romance language at Columbia University, was persuaded by a French Professor, Lanson, to include Leguat's Relation in his study of "Extraordinary Voyages", published in 1920. Atkinson declared the narrative imaginary and its true author to be Misson. The heresy was dealt with in a Doctorate thesis presented by Alfred North Coombes in 1979, at Monash University, Australia, entitled: The Vindication of François Leguat (1991).

The Réunion Solitaire, Threskiornis solitarius (Selys-Longchamps, 1848)

Bontekoe attributed the name Dod-eersen to the fat bird he remembered to have seen at Saint Paul 's bay in Réunion Island , in a narrative written 27 years after his visit in 1619. He had never been to Mauritius but had probably read Van Neck's Relation (1601) which must have suggested the funny drawing he made of a wispy Dodo.

Tatton's Report published earlier, after a landing on the east coast with Captain Castleton in 1613 to victual their ship The Pearl, had simply mentioned the presence of fat, tame, turkey-sized Fowls, white of plumage. The crew, prospecting inland, discovered a pond "covered with ducks and geese" in which they fished large eels, probably Grand Etang (Fig. 2). The fat white birds described could have been the juvenile form of the extinct Réunion Solitary Ibis discussed further, which, like its Aldabran relative, Threskiornis aethiopica abbotti, displayed a white-plumaged head and neck (Beamish, 1970). It could be supposed that these parts did not become denuded as in the related mature Malagasy form Threskiornis aethiopica Latham to show a black skin, as this would have most certainly attracted the attention of the early visitors and been mentioned by them.

Later, when studying reports of early travellers to Réunion that kept mentioning a large solitary bird with feet like a Jungle Fowl's, a long neck and a white and black plumage, naturalists like Rothschild and Hachisuka, referring to Leguat's descriptions of the Rodrigues Solitaire, had concluded that there were two Raphid birds living at the same time on the island: a White Dodo and a Solitaire.

Paintings of White Dodos, alleged to have been brought to Europe, confirmed their opinion, contra Cheke (1987) and Fuller (1987), who thought they could have been representatives of albino birds or of naturalized bleached birds from Mauritius. It is to be regretted that neither Abbé Carré nor Sieur Dubois, who left fairly detailed descriptions of the avifauna, did not give even a rough sketch of the Solitaire.

The Réunion Solitaire was described, hunted and enjoyed as game by many early visitors, whose reports were gleaned and presented in a delightful way in a now rare book "Sous le signe de la tortue, voyages anciens à l'Ile Bourbon" (1611-1725), published in Paris by Professor Albert Lougnon in 1958. Barré and Barau give many quotations from these visitors in their Guide to Réunion Birds (1982).

In contrast, the myth of the White Dodo, attractive in itself, has impregnated the Réunion folklore and has recently motivated artists to represent the bird as a hero, in a series of adventures along 65 episodes of animated drawings, which the author enjoyed as a preview in an R.F.O. television programme from Réunion (Dedans, 1995). The text is to be translated in many languages. We can conclude that the White Dodo has found at last a fitting place, enthroned on the universal podium of animated movies, between Mickey Mouse and the Pink Panther. The staggering cost of the project, mentioned to be 33 M Francs, is just another homage to Wonderland.

In April 1974, B. Kervazo started searching for clues by excavating two caves near Saint Paul , known to have sheltered the first settlers of Réunion. He was rewarded by discovering the sub-fossil bones of a few extinct species listed by Sieur Dubois, probably the best chronicler of the pristine avifauna. They were: Flamingo, Sheld-goose, Night heron, Kestrel, Coot and Owl. In November of the same year, Cowles (1987) visited Caverne Vergoz retrieving the remains of two extant birds and a few bones of an endemic tortoise, Geochelone sp. Another coastal cave in Saint Paul 's area yielded further tortoise bones and the interesting relict of a large skink still extant at Round Island , Mauritius.

A timely communication to Nature by Mourer-Chauviré, Bour and Ribes (16 February 1995 ), revealed that intensive prospections have been carried out recently in three localities of Réunion island, including the Marais de l'Hermitage (Fig. 2). No raphid remains have been identified. However the bones of an extinct Ibis, Borbonibis latipes were always present, occurring in large number in the above-named Marsh.

A study of the bones disclosed the affinity of the bird to the genus Threskiornis. The discovery in 1994 of a lower mandible measuring 12.5 cm indicated that the bird had a shorter and less curved bill than in Threskiornidae, which tallied with Dubois' description of the Solitaire's bill, and with the way the bird fed according to Feuilley (1704). He had reported: "their food is but worms and filth it takes over or in the soil." In comparison the Rodrigues Solitaire's bill was shorter, wider (2.6 cm) and sharper, well adapted to tearing open fibrous fruits, which went with a muscular gizzard and the presence of a gizzard stone as in the Dodo. The Réunion Solitaire was a favourite food with the first settlers and the visitors. According to Abbé Carré (1667) its flesh was exquisite: "it is one of the best game in this country and could prove a choice meat at home. We wanted to keep two of these birds to send them to France to His Majesty, but as soon as they were kept on board, they died of melancholy, refusing to eat or drink."

The presence of a gizzard stone, a Raphid's trait, would soon have been detected in such a common game, had it existed, before abusive hunting forced it to its last retreat on the mountain tops. This important missing clue seems to have been overlooked both by Oudemans (1917) and Hachisuka (1953) when discussing the Réunion Solitaire/Dodo identifications.

The authors concluded that since the remains of all the birds described by early travellers had been found so far, except those of the Solitaire, one could presume the Ibis fitted this identity and more so if one added some items of Dubois' description : long legs, white plumage with tip of wings and tail black and bushy ostrich-like tail. The bird's morphology suggested to them that it could be related either to the Sacred Ibis, T. aethiopicus or to the Straw-necked Ibis, T. spinicollis. In conclusion they renamed the bird: Threskiornis solitarius (Selys-Longchamps, 1848), "Borbonibis latipes being a junior synonym" (Mourer-Chauviré, Bour, Ribes, 1995).

The Sacred Ibis was revered in ancient Egypt as the incarnation of Thoth, god of learning and wisdom. In 450 B.C., Herodotus recorded that it was depicted on murals in its marshy environment, whilst mummified birds were found in tombs. It is found now only south of the Sahara as far as the Persian Gulf, and has reached southern Africa and Madagascar where Bonaparte, on slight plumage differences, sub-specified it to Threskiornis aethiopica Bernieri. It reached eventually the Aldabra Atoll to the north and the Mascarenes to the South, as proved by the present sub-fossil findings.

As it is often the case with the isolation of a newly arrived stock in an oceanic island, variations developed in the Aldabran bird, which now displays bright blue eyes and a white-plumaged head and neck in the juveniles, which justified its classification as Threskiornis aethiopica abbotti by Ridgway (1895) when he examined the specimens that Abbott had collected on Aldabra in 1892. Juveniles are cared for a long time by their parents before maturing after two years (Guérin, 1949).

In pristine Réunion, the avifauna was observed by early visitors to effect an annual vertical migration to adapt to climatic changes and food availability. The endemic olive White-eye, Zosterops o. olivacea, is still an example as it flies in September each year up the slopes to the 500-1900 m belt to feed and reproduce amongst the pollen-rich clusters of blooming Hypericum. Dubois had observed that: "All the birds of this island have their season each in its specific time, staying six months in the flat country and six months up the mountains from which they come back in a fatty condition and good to eat." However, he further added: "I except. the River birds and the Solitaire, the partridges and the Blue Birds (Porphyrio sp.) which do not change." He probably meant that they did not come back in an overfat condition, though he shared in the opinion of nearly all the early visitors, that the Solitaire was amongst "the best game in the island."

The discovery of an Ibis lower mandible in l'Hermitage Pond in 1994, not only confirmed the bird's identity, as already pointed out, but seems to reveal through its shortness and straightness an adaptation to feed on the harder soil of the forest floor, a place it was observed to retire to for six months in the year. This trait seems to have evolved also in its Malagasy cousin, the endemic Crested Wood Ibis, Lophotibis cristata Boddaert, which also displays a shorter and less curved bill than observed in the tribe, more suited to feed in the moist habitat of the forest by digging vigorously in the soil "to catch small vertebrae, insects, spiders, worms and molluscs" (Milon, Petter, Randrianasolo, 1975).

According to Mourer-Chauviré, Bour and Ribes, examination of the Réunion Solitaire's bones has disclosed its ability to fly in spite of Dubois' observations: "it is caught by running after it, as it flies very little." The Malgache crested

Wood Ibis' behaviour in about the same circumstances seems to suggest an answer, as reported by Milon, Petter and Randrianasolo (1975): "the bird laboured to fly noisily when surprised, to land a little bit farther on the ground or to perch on a branch." The Wood Ibis nests in trees.

The other stand-in candidate for the Solitaire's role proposed by Mourer-Chauviré, Bour and Ribes, is the Straw-Necked Ibis of Australia, Ibis spinicollis. It has white underparts, a black back and a long white neck, tinged with yellow and approaches the image of the Solitaire as described by Abbé Carré: "it has a beautiful plumage veering on yellow, with long legs". Feeding on grasshoppers and insects, it is a useful bird nesting near swamps on low trees, or in reeds on a platform of herbage where three dull white eggs are laid.

An occasional visitor to Tasmania, it could have reached the Mascarenes which have acquired through the times and from the East: bats, swiftlets and the most beautiful of their pigeons, Columba mayeri, the Mauritius Pink Pigeon, a close relative to the White-head Pigeon of Australia, Columba leucomela.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

With the disappearance of the White Dodo as the Réunion ornithological emblem, new symbols should be reappraised for the Mascarene Islands. In the case of Mauritius, the heraldic Grey Dodo has been confirmed by tradition in the noble charge of holding the national coat of arms. For Rodrigues the Solitaire, proud of gait, is an evident choice. As for Réunion, the Ibis being already the badge of the British Ornithologists Union, it could be suggested that the endemic Réunion Harrier, Circus maillardi maillardi, a superb bird of prey, should be allowed to top the totem pole of the island.

Note

- Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (1974) Poultry Nutrition, H.M.S.O., London

- 2 C.A.B. International (1987). Manual of Poultry Nutrition in the Tropics, C.A.B. International, Wallingford , U.K.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks go to those who helped by providing advice and data for the working of this paper:

Dr John Williams, who obligingly read the proofs, identified insect invaders associated with fallen Latan fruits and provided useful comments.

Mr. Pierre Bourgault du Coudray, who kindly lent me the 1995 Exhibition Catalogue of the Zoology Museum of the University of Amsterdam entitled Dodo, Raphus cucullatus (Didus ineptus) by Ben van Wissen, and allowed me to examine and photograph the Dodo gizzard stone he found at La Mare aux Songes site.

Mr. A. Hamid Mohungoo, from the Chemical Division of the Ministry of Agriculture, who performed the chemical analysis needed to determine the fattening elements in the fruits of Mascarene Palms and Pandanae and in some forest endemics.

Dr. Christine Halais, who calculated the dietetic value of these elements in regard to the Dodo and the Rodrigues Solitaire.

Messrs. A.W. Owadally, Conservator of Forests and J. Guého, Curator of the Mauritius Herbarium, MSIRI and his assistant, Miss Danielle Florens, for discussing botanical data and help in the field.

Mr. A. Hosanee of the MSIRI, for drafting the schematic maps of the three Mascarene Islands.

Dr. Karl Jones, for providing references from his personal library.

REFERENCES

BARRE, N. AND BARAU, A. (1982). Oiseaux de la Réunion. Imprimeries Arts graphiques Moderne, St Denis, Réunion.

BEAMISH, T. (1970). Aldabra Alone. Georges Allen & Unwin Ltd, London.

BENVAN WRISSEN, R. (1995). Dodo, Raphus cucullatus (Didus ineptus). Catalogue of the Exhibition "The fate of the Dodo". Isp/Zoologisch Museum Universiteit Amsterdam".

BERG, C.C. & VAN HEUSDEN, E.C.H. (1985), Moracées. 164. Flore des Mascareignes. MSIRI. ORSTOM. Royal Botanic Gardens. Kew.

BERLIOZ, J. (1941). Oiseaux de la Réunion. Faune de l'Empire Français. 4 Paris: Larose.

BOUTON, L. (1866). Report of the Secretary at the Annual Meeting. Proc. Roy. Soc. Arts and Sci. Maurit. New series. Vol. II : 261-264.

BROM, T.G. (1991) The diagnostic and phytogenic significance of feather structures, Thesis. Institute of Taxonomic Zoology, University of Amsterdam.

BROM. T.G. AND PRINS, T.G. (1988). A skeleton of the Dodo, Raphus cucullatus (L.) new to Ornithology. Bid jdr. Dierk. 58: 155-158.

BROM, T.G. AND PRINS, T.G. (1989), Microscopic investigation of feather remains from the Head of the Oxford Dodo, Raphus cucullatus. J. Zool. Lond.: 218, 219, 233- 246.

CADET, Th. (1980). La végétation de 1'I1e de la Réunion. These, Saint Denis de la Réunion.

CAUCHE, F. (1651). Relation du Voyage que François Cauche de Rouen a fait à Madagascar, isles adjacentes et côte d'Afrique. Recueilly par le Sieur Morisot avec notes et marges. Paris: Augustin Courbe.

CHEKE, A.S. (1987). Ecological History of the Mascarenes with particular reference to extinction and introduction of Vertebrates Apud Studies of Mascrene island birds. Ed. A.W. Diamond. Cambridge University Press.

CHEKE, A.S., GARDNER, T.A.M., JONES, C.G., OWADALLY, A.W. AND STAUB, F. (1984, 1985). Did the Dodo do it ? Animal kingdom 87 (1): 4-6.

COWLES, G.S. (1987). The Fossil Record. Apud Studies of Mascarene Islands birds. Ed. A.W. Diamond. Cambridge University press.

CRACRAFT, J. (1974). Physiology and evolution of the Ratite birds. Ibis 115, 494-521.

DEDANS, M. (1995). Tout guilleret, dodo fait des yeux doux à Walt Disney. Report of an interview with H.E. Michel Dedans, Mauritius Ambassador to Switzerland, Week end, 17.12.95.

DUPON, J.F. (1973). Relation de l'isle Rodrigues. Texte attribué à Tafforet c. 1776. Proc. Roy. Soc. Arts Sci. Maurit. 4(1) : 1-16.

FULLER, E. (1987). Extinct Birds. Facts on file publication. New York.

GUERIN, R. (1940-1943). Faune ornithologique ancienne et actuelle des Îles Mascareignes, Seychelles, Comores et des îles avoisinantes. 3 vols. Port Louis. Mauritius General Printing and Stationery Ltd.

HASHISUKA, M. (1953). The Dodo and kindred birds, or the extinct birds of the Mascarene Islands. London I.H.F and G. Witherby.

HILL, R. (1968). Australian Birds. Thomas Nelson. (Australia) Ltd.

KITCHENER, A.C. (1993). a. On the external appearance of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus (L.) (17758). Archives of Natural History. 20(2): 279-301.

KITCHENER, A.C. (1993) b. Justice at last for the Dodo. New Scientist. (28.8.93).

LEGUAT DE LA FOUGERE, F. (1708) Voyages et aventures de François Leguat et de ses compagnons en deux isles désertes des Indes Orientales. 2 vols. Amsterdam: JL. de Lorme.

L'ESTRANGE, Sir H. (1836). In Brown, Sir Thomas (1836) Works. Wain ed. London 1 Vol I. p. 369, Vol. 2 p. 173 (apud Fuller, E. 1987).

LOUGNON, A. (1970). Sous le signe de la tortue. Voyages anciens à 1'Île Bourbon (1611-1725), 3rd ed. St Denis, Réunion (Author).

MILLON, P. PETTER, J.J. AND RANDRIANASOLLO, G. (1973). Oiseaux, xxxv. Faune de Madagascar. ORSTOM., Tananarive. CNRS, Paris.

MONTAGIONI, L. AND NATIVEL, P. (1988). La Réunion. Î1e Maurice, Géologie et Aperçus Biologiques. Plantes et Animaux, Masson, Paris.

MOORE, H.E. JR. AND GUEHO, J. (1984). Palmiers, 189. Flore des Mascareignes. MSIRI. ORSTOM.. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

MOURER-CHAUVIRE, C.BOUR, R. AND RIBES, S. (1955). Was the Solitaire of Réunion an Ibis? Nature. Scientific Correspondence (373) 568.

NORTH COOMBES, A. (1991). The Vindication of François Leguat. Editions de l'Océan Indien. Mauritius (1st ed. 1979).

OUDEMANS, A.C. (1917). Dodo studien. Johannes Müller. Amsterdam.

PAULIAN, R. (1961). La Zoogéographie de Madagascar et des Iles voisines. Faune de Madagascar XIII. Institut de Recherches Scientifiques, Tananarive.

PINGRE, G.(1763c). Voyage à l'Ile Rodrigues. Ms 1803. Bibliothèque Ste Geneviève, Paris.

PITOT, A. (1905). Teylandt' Mauritius. Esquisses historiques (1598-1710), précédées d'une notice sur la découverte des Mascareignes et suivies d'une monographie du Dodo, des Solitaires de Rodrigues et de Bourbon et de l'Oiseau Bleu. Port Louis, Mauritius. Coignet Frères & Cie

RIDWAY, R. (1895). On birds collected by D.W.L. Abbott in the Seychelles. Amirantes, Gloriosa, Assumption, Aldabra and adjacent islands. Proc. Unit. St. Nat. Mus. 18(18): 530.

RIVALS, P. (1952). Etudes sur la végétation naturelle de 1'Î1e de la Réunion. Thèse, Toulouse, 214 pp.

SADDUL, P. (1995). Mauritius. A geomorphological Analysis. Geography of Mauritius Series. Mahatma Gandhi Institute, Mauritius.

STAUB, F. (1971). Actual situation of the Mauritius endemic birds. Bull. ICBP II : 226-227.

STAUB, F. (1976). Birds of the Mascarenes and Saint Brandon. Port Louis, Mauritius. Organisation Normale des Entreprises.

STAUB, F. (1977). Dodos et Tambalacoques. Le Cernéen. Mauritius 15.10.77: 1 & 3.

STAUB, F. (1973). Birds of Rodriguez Island. Proc. Roy. Soc. Arts Sci. Maurit. 4(1): 17-59.

STAUB, F. (1993). Fauna of Mauritius and associated Flora. Precigraph Ltd. Mauritius.

STAUB, F. (1994). La controverse du Dodo, Week End, 1.5.94.

STAUB, F. AND GUÉHO, J. (1968). The Cargados Carajos Shoals or St. Brandon: resources, avifauna and vegetation. Proc. Roy. Soc. Arts Sci. Maurit. 3: 7-46.

STRICKLAND, H.E. AND MELVILLE, H.G. (1848). The Dodo and its kindred. London: Reeve Benham and Reeve.

STORER, R.W. (1970). Independent evolution of the Dodo and the Solitaire. Auk 87: 369-370.

STRAHM, W. (1989). Plant Red Data Book for Rodrigues. Koeltz Scientific Books, Koningstein's Germany.

TATTON, J. (1625). A journal of a voyage made by the Pearle to the East India wherein went as Captain Master Samuel Castleton of London , and Captain George Bathurst as Lieutenant. Perchas (ed.)

TEMPLE, S.A. (1983). The Dodo haunts a forest. Animal kingdom 86 (1).

VAN NECK, J.C. (1601. Second livre, Journal ou Comptoire contenant du Voyage fait par les huit navires d'Amsterdam au mois de mars, l'an 1598. fol Amsterdam, 1601 (Journal de l'Amiral Cornelius Van Neck) Traduction latine de Bibaldus Stroebus Silesius, De Bry fratres; Frankfort. Quinta pars Indiae Orientalis.

VAUGHAN, R.E. AND WIEHÉ, P.O. (1937). Studies of the Vegetation of Mauritius. I A Preliminary Survey of the Plant Communities. J. Ecol. 25: 289-343.

VAUGHAN, R.E. AND W1EHÉ, P.O. (1941). Studies of the Vegetation of Mauritius. IH The Structure and Development of the Upland climax forest. J. Eco!. 29: 127-160.

VINSON, J. (1956). Notes d'Histoire Naturelle. I. L'oeuf du Dodo. Proc. Roy. Soc. Arts Sci. Maurit. I (4) : 313-315.

VISON, J. (1967). Le Centenaire de la découverte à l'Ile Maurice des ossements du Dronte ou Dodo. Raphus cucullatus Linne. Proc. Roy. Soc. Arts Sci. Maurit. 3: 1-5.

WiEHi, P .0. (1949). The vegetation of Rodrigues Island. Bull. Mauritius Inst. 2: 280-303

Préambule | Les mystères d’un nom | Dodoland | Témoins oculaires | Des contradictions évidentes | Premières légendes | Derniers témoins | Physionomie du Dodo | Le Dodo de Prague | Le Dodo de Surat | Le Dodo d'Amsterdam | Des Dodos blancs | L'image déformée d'une image déformée | Où est la vérité ? | Quels vestiges ? | Mais d'où sort-il cet oiseau ? | Injustice pour tous les autres | Les tortues géantes Cylindraspis | Quel régime alimentaire ? | Symbiose avec les tortues ? | Le Dodo d'Alice |Frère du Dodo| Découvertes du solitaire | Evolution | As dead as the Dodo ? | Conclusion ? | Bibliographie | Questionnaire destiné aux scolaires | Le Dodo a désormais son Musée virtuel | Réactions | Presse | Contemporains disparus | Dodo and solitaires, myiths and reality | Texte de Buffon consacré au Dronte | Louis Etienne Thirioux | Short communications | Emmanuel Richen sonne "Le Reveil du dodo" | Le reveil du dodo | Il faut sauver le dodo | The intercultural dodo | Sous la varangue | Des dodos comme s'il en pleuvait !!!... | Le Dodo de Lausanne | Sur la piste du Dodo | Speculation, statistics, facts and the Dodo’s extinction date

Avan teks | Mister enn non | Dodoland | Temwen vizyel | Enn ta kontradiksyon | Premye lezann | Dernye temwen | Dodo la so portre | Dodo Prag la | Dodo Surat | Dodo Amsterdam | Bann Dodo blan | Zimaz enn zimaz enn zimaz,… | Kot laverite ? | Ki pe reste aster ? | Dodo la, ofe ki li ete ? | Pa Dodo selman | Bann torti zean, fami Cylindraspis | Ki zot ti pe manze ? | Ki zot ti pe manze ? | Sinbyoz1 ek torti ? | Dodo Alice | Dodo la so frer | Dekuvert soliter | Evolisyon | Konklizyon ? | Bibliographie | Kestyoner pu bann zelev