| Kaz | Enfo | Ayiti | Litérati | KAPES | Kont | Fowòm | Lyannaj | Pwèm | Plan |

| Accueil | Actualité | Haïti | Bibliographie | CAPES | Contes | Forum | Liens | Poèmes | Sommaire |

Le musée du Dodo

PROCEEDINGS OF THE

ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

OF MAURITIUS

Vol. VII - 2004

Short communications

1. Review of three books just published on the Dodo

FULLER. Errol. Dodo - From extinction to icon. 180 pages. numerous colour & monochrome plates. London: HarperCollins. 2002, Hardback £16.99. ISBN 0007145721.

HENGST, Jan den. The Dodo. The bird that drew the short straw. 119 pages, many illustrations. Marum, Netherlands: Art Revisited 2003. Price not given. ISBN 9072736265.

PINTO-CORREIA, Clara. Return of the crazy bird. The sad strange tale of the Dodo. 216 pages, some text illustrations. New York: Springer-Verlag/Copernicus Books, 2003. £21. ISBN 0387988769.

Like Mahébourg buses, you wait ages for a Dodo book, then several come at once. First out was Fuller's Dodo, followed rapidly by the other two.

Given the limitations of the subject - a species known from a few meagre contemporary accounts and pictures, some reconstructed skeletons and a single surviving head and foot - it is remarkable what a variety of very different books have been generated about it. As virtually nothing is known of the bird's biology, the books are largely reduced to emphasising different aspects of' what little is recorded in history and palaeontology - extended by some speculation of variable ment. There is a regrettable tradition, traceable back to Buffon but wildly extended by A. C. Oudemans in his Dodo studien (1917) and M. Hachisuka in The dodo und indred birds (1953), of stretching the evidence to generate all sorts of factoids that then reverberate endlessly in the tertiary literature. While Fuller is at pains to avoid this trap, the other two books suffer from this legacy, and indeed Pinto-Correia's offering is inextricably enmeshed in it.

Return of the crazy bird is a translation of a Portuguese original from 1994, barely updated, though nowhere is this acknowledged in this Arnerican version - Hengst's bibliography gives away the guilty secret. The most important contributions from the last decade are thus absent from Pinto-Correia's book, apart from a cameo reference to Beth Shapiro's DNA studies (Science 295:1683, 2002). As Mauritius, the Dodo's home island, was originally discovered by Portuguese navigators, one might have hoped a Portuguese author would have added something from the opaque period in the 16 th century before the Dutch arrived with much fanfare in 1598. But no, nothing new there. Worse, Pinto-Correia regurgitates many discredited 'facts' from earlier works: that the Portuguese released monkeys and goats in Mauritius (it was the Dutch), that there was a dodo, or rather two, in Réunion (there was an ibis, no dodos), that Dodos were last seen in 1681 (the last reliable report was in 1662) etc. To further a century myth, the author even misquotes Shapiro to place Didunculus as the `intermediary link between the pigeons of Europe [sic] and the crazy birds of the Mascarenes' - the Dodo's closest relative was the Nicobar Pigeon Caloenas.

Provided caution is maintained at all times. Return of the crazy bird is not without interest. Pinto-Correia discusses at sonie length the significance of Emperor Rudolf II's collections in early 17 t h century Prague, and the career of his protegé, the Dodo's principal iconographer Roelant Savery. Her chronology of his paintings differs (as does Hengst's) from that of the most assiduous recent Savery specialist, Kurt Müllenmeister. She also looks at the development of'dodology' in the 19th century against the background of bitter scientific rivalries in Britsh academia - Owen, Strickland, Darwin etc. Oh yes, the weird title: passaro doudo is 'crazy bird' in old Portuguese - though there is no direct evidence, Sir Thomas Herbert notwithstanding, that the 'Portuguize' ever so named the bird.

Pinto-Correia's book has just a bare minimum of monochrome illustrations; Hengst, by contrast, has assembled an apparently complete collection of Savery's Dodo paintings (mostly well-reproduced in colour), and also includes most of the other important early images. While his speculation that Savery based everything on a single stuffed specimen in Prague, and that he varied the bird's colour arbitrarily to suit his lighting scheme for a particular painting, are open to debate, there is much of value here. Hengst devotes a chapter to Dodo reconstructions, relating skeletons to old painting and drawings. confirming that Mansur's Indian miniature is the most anatomically accurate rendering. Another chapter is on likely food and ecology (with a table of fruiting seasons of Mauritian trees) - though France Staub's similar investigations (Proc. Rov. Soc. Arts Sc i. Mauritius 6:89-122, 1996) are not cited. He covers the historical background and the early accounts adequately, and is at pains to debunk the 'phantom' of the Réunion or White Dodo. He gives a last date of 1688, but this is based on Lamotius's reports of'dodaarsen' (without accompanying descriptions) 20 years after the name had transferred to another flightless bird, the Red Hen Aphanapteryx bonasia. Like Fuller, Hengst devotes some enjoyable space to dodo trivia - indeed his claim to fame on the jacket blurb is as 'president of the Dodological Society'!

Two editions of Extinct birds and a substantial monograph on the Great Auk Alea impennis have established Fuller's credentials as a chronicler of vanished species, so it is no surprise that he should turn his attention to the Dodo and the Rodrigues Solitaire Pezophaps solitarius. Fuller accepts the re-assignment of the Réunion Solitaire to the ibis Threskiornis solitarius, but can't restrain a sneaking hope that there may also have been a dodo there.

Like his earlier books, the text is embellished with a wide selection of historical illustrations, but Dodo is a slighter wok, and here we unexpectedly find Fuller's polemical side. He is scathing about 'the remarkably poor scholarship' of many past publications on the Dodo and the Solitaire (or 'Solitary' as he calls it, after Leguat's first translator). While there is indeed much to criticise in Oudemans's and Hachisuka's books. Temple 's mutualism-with-tree-seeds hypothesis and Atkinson's intellectually dishonest attempts to discredit Leguat, Fuller dismisses these works with little serious discussion. Indeed one ends up feeling that Fuller thinks all post-Victorian Dodo research is weak, though some of us come through a little better, being only mildly damned with faint praise. I have to agree that Strickland's exceptional 1848 monograph has been a hard act to follow. but since he talks of the Dodo's emerging relationship with Caloenas, it would have been nice to have credited Shapiro & Co!

That said, Fuller's book is an enjoyable popular introduction to the dodo's history and its impact on cultural perceptions - from Alice in Wonderland, via obsessive collectors of'dodo trivia', to all the kitsch stuff offered to tourists here in Mauritius.

Unfortunately Fuller's pictures are patchily reproduced - definition is often poor and the colour balance of many of' the historic dodo paintings and photos of Mauritian scenery is well below acceptable standards - the author tells me he tried to get the publisher to use better paper, without success.

Any recent Dodo book has to be measured against Ben van Wissen's exhibition catalo g ue volume. Dodo. of 1995. None of them approach it for overall completeness of historical and anatomical detail, though some (Ziswiler's Der Dodo of 1996. Hengst) do better on pictures, and others (Fuller, Hengst) on the Dodo as icon of extinction. Unlike the others, Pinto-Correia's book has an explicit context in the wider history of science. but this is no excuse for filling it with out-of-date and inaccurate information about the bird itself. Hengst and Fuller had the good taste to visit Mauritius before writing their books.

Anthony Cheke

[adapted from reviews that first appeared in The Ibis, journal of the British Ornithologists ' Union]

|

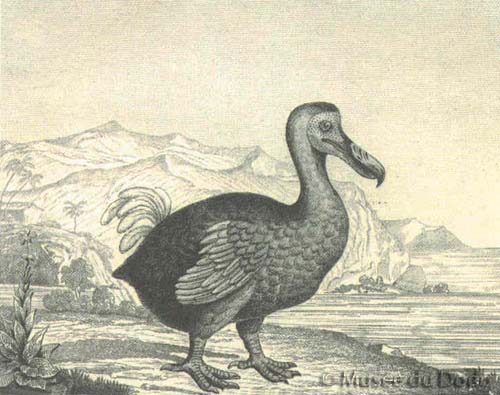

Gravure de la fin du XVIIIe siècle. |

Préambule | Les mystères d’un nom | Dodoland | Témoins oculaires | Des contradictions évidentes | Premières légendes | Derniers témoins | Physionomie du Dodo | Le Dodo de Prague | Le Dodo de Surat | Le Dodo d'Amsterdam | Des Dodos blancs | L'image déformée d'une image déformée | Où est la vérité ? | Quels vestiges ? | Mais d'où sort-il cet oiseau ? | Injustice pour tous les autres | Les tortues géantes Cylindraspis | Quel régime alimentaire ? | Symbiose avec les tortues ? | Le Dodo d'Alice |Frère du Dodo| Découvertes du solitaire | Evolution | As dead as the Dodo ? | Conclusion ? | Bibliographie | Questionnaire destiné aux scolaires | Le Dodo a désormais son Musée virtuel | Réactions | Presse | Contemporains disparus | Dodo and solitaires, myiths and reality | Texte de Buffon consacré au Dronte | Louis Etienne Thirioux | Short communications | Emmanuel Richen sonne "Le Reveil du dodo" | Le reveil du dodo | Il faut sauver le dodo | The intercultural dodo | Sous la varangue | Des dodos comme s'il en pleuvait !!!... | Le Dodo de Lausanne | Sur la piste du Dodo | Speculation, statistics, facts and the Dodo’s extinction date

Avan teks | Mister enn non | Dodoland | Temwen vizyel | Enn ta kontradiksyon | Premye lezann | Dernye temwen | Dodo la so portre | Dodo Prag la | Dodo Surat | Dodo Amsterdam | Bann Dodo blan | Zimaz enn zimaz enn zimaz,… | Kot laverite ? | Ki pe reste aster ? | Dodo la, ofe ki li ete ? | Pa Dodo selman | Bann torti zean, fami Cylindraspis | Ki zot ti pe manze ? | Ki zot ti pe manze ? | Sinbyoz1 ek torti ? | Dodo Alice | Dodo la so frer | Dekuvert soliter | Evolisyon | Konklizyon ? | Bibliographie | Kestyoner pu bann zelev