| Kaz | Enfo | Ayiti | Litérati | KAPES | Kont | Fowòm | Lyannaj | Pwèm | Plan |

| Accueil | Actualité | Haïti | Bibliographie | CAPES | Contes | Forum | Liens | Poèmes | Sommaire |

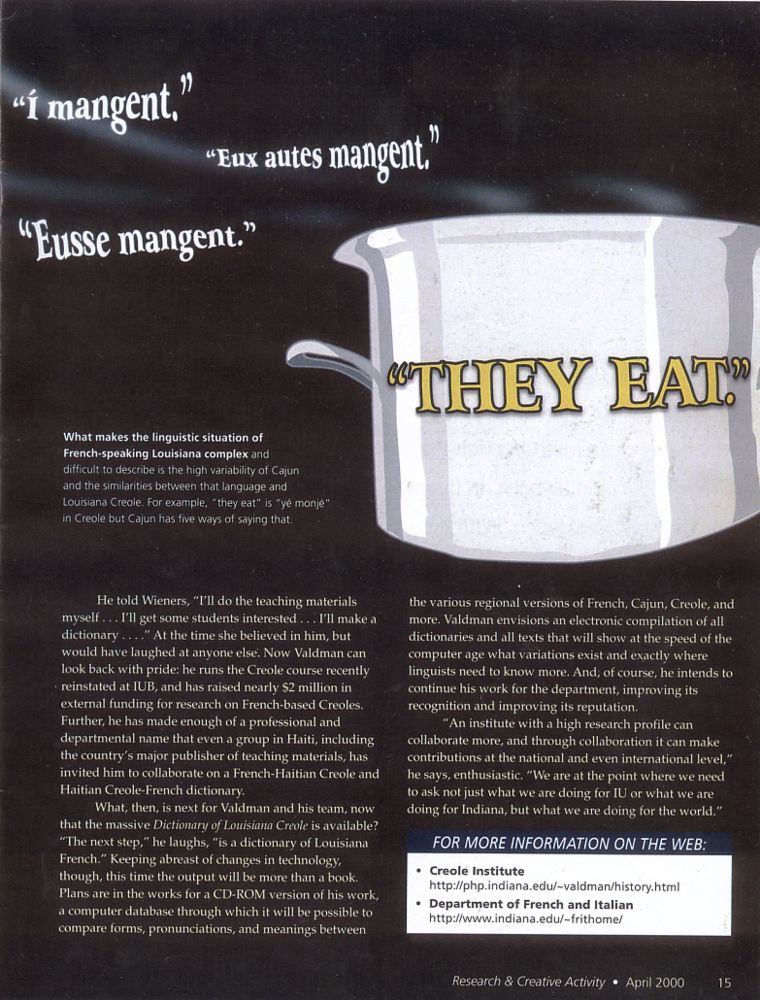

“Book of Changes: the preservation of Creole, a nuanced language,

is a task as complex as the many-sided history of Louisiana”

(Research & Creative Activity, Vol. XXIII, No. 1, April 2000. Indiana University)

(by William Orem)

|

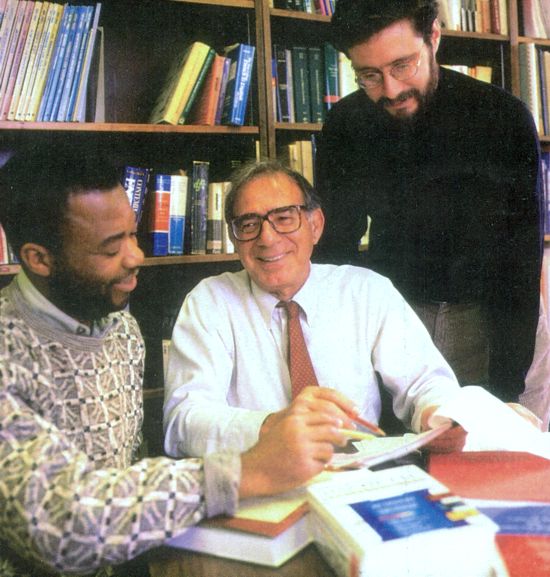

Albert Valdman, Rudy Professor of French and Italian and Linguistics, Indiana University Bloomington, talks with Emmanuel W. Védrine (left), a graduate student in French linguistics and a Haitian native, and Don Reindl, a doctoral student in linguistics, about Creole and Cajun research. |

Whether "Creole" brings to your mind a spicy gumbo, a Caribbean patois, or a Louisiana family tracing its ancestors to France or Senegal, you're on the right track. Anything "creole" needs a cultural mass spectrometer to isolate how Old World origins recombined with New World influences to forge a unique taste or language or people.

The Creole Institute at Indiana University (IIU) Bloomington itself has resulted from the melding of old and new. The combination began in 1960, when the Indiana University Bloomington French department, with a strong tradition of teaching language through literature, hired linguist Albert Valdman, now Rudy Professor of French and Italian and Linguistics. He laughs at the memory of how volatile that mix seemed four decades ago. "Traditional literature-oriented foreign language college teachers were afraid that, as was the case at Cornell, linguists would take over language instruction," he smiles. "People thought that hiring a linguist was asking for trouble."

While he has not lived up to the label of troublemaker, in nearly forty years of work at IU Valdman has radically changed the face of the department – and even the university. As the director of language instruction, he has devised what is by many standards the best associate instructor training program on campus, along with a unique system of mentoring future specialists of French language instruction. He pioneered a special graduate tract:- in French linguistics, one of only a handful in the United States. The reputation of the program draws top linguists here (currently there are five). And his voice sounds satisfied when he describes how students from New York, Miami, Boston, and other places with large Haitian populations have in the past corne here – to south central Indiana – to learn Haitian Creole.

Another Creole – this time of the Louisiana variety – has been the focus for Valdman and a small team of coworkers for the past five years. The result of their labors is the recently published Dictionary of Louisiana Creole, documenting g to a high degree of specificity the use, pronunciation, shades of meaning, and regional affiliation of words in a vanishing language. The construction of such a dictionary was a daunting task, even to professionals, and its completion a sign of the academic robustness of Valdman and his team.

So what makes Louisiana such a simultaneously ripe and difficult location for linguistic research? The answer is history.

Around the turn of the eighteenth century, the area we now call Louisiana was home to French colonists coming either directly across the Atlantic from France or circuitously by way of Canada (though only somewhat; " Louisiana of the time stretched north and west tremendously farther than the state that bears the name today). These speakers of Vernacular French were living in a plantation economy; which is to say that Africans, bearing their own cultural and linguistic histories, were being forcibly brought in to work the land for French profit. Again the route was circuitous: many African slaves labored not in Louisiana at all but clown in the Caribbean in Martinique, Guadeloupe, Saint Kitts and – most prominently – Santo Domingo (modern-day Haiti). Though modern linguists do not know to what extent Louisiana Creole was created in Louisiana and to what extent it was influenced by Caribbean Creoles, there were huge influxes of different groups into Louisiana at this time. History moved, and the language pot stirred.

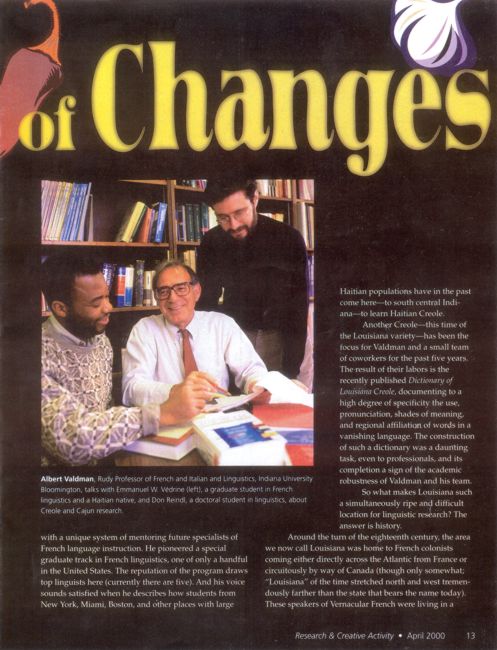

Currently some 30,000 native speakers of Creole live in Louisiana, though almost none are "monolinguals" – that is, none use Creole as their only language. Because of the same progress of history, not French but English is now the predominant language in Louisiana, and Creole itself is rapidly disappearing. Valdman's work seeks to record and preserve this nuanced language before it is gone, but the tank is as complex as the many-sided history of the region. In 1765, as another example, a group of Acadian French was driven from their homes in modern-day Nova Scotia by the British and some relocated in Louisiana; their regional version of French we now know as Cajun. The List of possible influences could go on, but the point is made: in seeking to preserve and document a specific Louisiana dialect, one must first strain it as far as possible from the bubbling mix of its neighbors.

In trying his band at this unlikely task, Valdman had the help of several other noted linguists, two of whom – Tom Klingler, an associate professor of French at Tulane University, and Kevin Rottet, an assistant professor of French at the University of Wisconsin at Whitewater – were his graduate students at IUB. "They conducted the field work," Valdman says casually, by which he means the momentous task of individually amassing and then, as a team, examining all written documents of Creole that could be found, from previous incomplete dictionaries to firsthand recordings to historie travelers' accounts. Their completed dictionary tells where a particular word is used, gives a direct quotation taken from the field research, followed by an English translation and a guide to pronunciation. ln the words of noted Creolist Glenn Gilbert, the book is "remarkable, a unique record of Louisiana French Creole... There is nothing else like it."

Valdman is amused to look back on where his interest in Creole began. Decades ago when he first met the woman who was to be his spouse, Hilde Wieners, she had just completed a documentary film on the Caribbean. Though his doctoral dissertation director at Cornell had also clone work in Haitian Creole, it was actually Wieners who sparked his interest in learning the language. Yet he found, to his amazement, no organized way to do so; the materials for the teaching of Creole simply did not exist.

He told Wieners, "I'll do the teaching materials myself ... I'll get some students interested … I'll make a dictionary ...." At the time she believed in him, but would have laughed at anyone else. Now Valdman can look bock with pride: he runs the Creole course recently reinstated at IUB, and has raised nearly $2 million in external funding for research on French-based Creoles. Further, lie has made enough of a professional and departmental name that even a group in Haiti, including the country's major publisher of teaching materials, has invited him to collaborate on a French-Haitian Creole and Haitian Creole-French dictionary.

What, then, is next for Valdman and his team, now that the massive Dictionary of Louisiana Creole is available? "The next step," he laughs, "is a dictionary of Louisiana French." Keeping abreast of changes in technology, though, this time the output will be more thon a book. Plans are in the works for a CD-ROM version of his work, a computer database through which it will he possible to compare forms, pronunciations, and meanings between the various regional versions of French, Cajun, Creole, and more. Valdman envisions an electronic compilation of all dictionaries and all texts that will show at the speed of the computer age what variations exist and exactly where linguists need to know more. And, of course, he intends to continue his work for the department, improving its recognition and improving its reputation.

"An institute with a high research profile can collaborate more, and through collaboration it can make contributions at the national and even international level," he says, enthusiastic. "We are at the point where we need to ask not just what we are doing for IU or what we are doing for Indiana, but what we are doing for the world."

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THE WEB:

- Creole Institute: http://php.indiana.edu/-valdman/history.html

- Department of French and Italian: http://www.indiana.edu/~frithome/

|

|

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

Courtesy of

E. W. VEDRINE CREOLE PROJECT, Inc.

![]()