| Kaz | Enfo | Ayiti | Litérati | KAPES | Kont | Fowòm | Lyannaj | Pwèm | Plan |

| Accueil | Actualité | Haïti | Bibliographie | CAPES | Contes | Forum | Liens | Poèmes | Sommaire |

The Agronomist:

Jean Dominique and Michele Montas' story universal appeal…

|

|---|

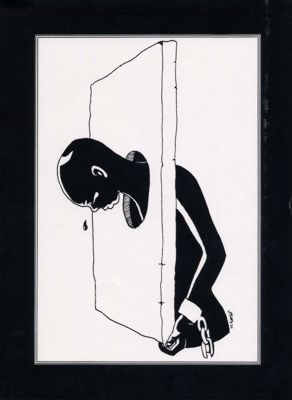

The weight of Slavery - Le poids de l'esclavage. Charlot Lucien. |

For millions of Haitians, the voice of Jean Dominique continues to shout in the microphone “Yo arete konpè Philo! Yo arete konpè Philo”! (They arrested Konpe Filo!). The year was 1980, and the Duvalier regim had decided to put a halt to the growing media contestation that had heightened the consience of the all social classes to unprecedented levels in Haiti. Intellectuals, artists, street vendors found their voices in the team assembled by Jeando and his wife Michele Montas. Wheter it was the then soft spoken voices of Manno and Marco, wheter it was the commanding and pointed analysises of Jeando, or the mocking tone of Konpè Filo, the regim had reasons to worry about their pervasive impact on the statu quo.

Predictably, Jean, Michele, their team and dozens of other Haitian media personalities were rounded up and sent in exile during the infamous Decembre noir of 1980. But the damage had already been done. Six years later, in 1986, after continuous protests, the 29 year-old regime fell in. Jean returned in Haiti the same year where he litteraly landed on the shoulders of the thousands of fans who had ran to the airport to welcome their hero. The optimistic vast smile, the pipe, the commanding voice, the V sign… the charm played again: in a matters of weeks, thousands of poor folks, wealthy busnissmen, starving artists, obscure and reknown intellectuals, stree vendors… had poured money in a never seen collection drive to raise the funds necessary to rebuilt Radio Haiti Inter.

In one of those tragedies of epic magnitude, Jean's blood was spilled in 2000, when he thought that he had come back to see democracy flourish in his country, leaving his spouse of 28 years at the helm of a radio targeted for 30 years for its commitment to the empowerment of the Haitian masses. Since then, Michelle Montas, while assuring the management of the radio, and seeking justice for the murder of her husband, has been the target of threats and one assassination attempt that left a body guard dead.

The story of Jean Dominique and Michel Montas goes beyond just the story of a Haitian radio station in Haiti and one man's dedication. This is a human journey that exemplifies the struggle of Haitians for justice, the pursuit of the truth even at the ultimate cost, the quest for a dream and the resilience of an idea and an ideal through a couple, than a woman.

This explain the interest of Jonathan Demme, producer of movie blocbusters such as Silence of the Lambs, Philadephia, in this couple. He befriended them in the 1980s, conducted numerous interviews with them, and later after Jean's assissination, released the documentary The Agronomist, which is having an international release this month.

This explains also an fascinating reaction I witnessed last year when I attended a special preview at the University of Massachusetts last year, with Michele Montas, and Wyclef Jean in attendance. Hundreds of young college students attended a conference in anticipation of Haiti 's bicentennial. A vast majority, I suspect was there for mega star Wyclef Jean. The profound, respecful silence, the gaps and the tears that I observed in the young audience toward the end of the movie, spoke volume to the universal appeal of Jean and Michele' story. That should give hope that that bridges can be built across geography and generations: these young folks weeping and sobing upon seeing the end of the movie, were doing so for the same man that thousands of somber peasants dressed in white cried for in April 2000 in Haiti thousand miles away, as they were speading Jean Dominique's ashes in their river, the Artibonite River.

THE INTERVIEW:

Jean Dominique and Michelle Montas: A hard to kill dream…

Jean Dominique and Michelle Montas ran Radio Haiti Inter in Haiti for 30 years and had known exile, threats and sabotage as they stood to telling the truth and question power at all costs. In 1980, the Duvalier regime exiled both of them and members of their team because of their broadcasting questioning the misdeeds of a dictatorship.

They returned in 1986 and, with the support of the population, rebuilt the radio and reconstructed their team. A dream never dies… Jean thought that his country was on the road to democracy… but died assassinated in 2000, ironically during the Aristide years. His assassins have never been officially found, and Michelle after numerous threats and one assassination attempt that left a bodyguard dead, left the country. Had she settled? Her emphatic no indicates that she is pursuing the dream and this month, the release of Jonathan Demme's The Agronomist, a tribute of Demme to his friend Jean Dominique, is bound to keep his memory and the struggle of the Haitian people at the forefront. As the film is being released to an international audience, with a special showing in Boston this month, it was a privilege to interview Michele Montas.

CL: Tell us something about the private Jean that people wouldn't know? Dealing with you, dealing with people in his private life…

Only his close friends knew about his unique sense of humor, a self-deprecating sense of humor that allowed him to laugh in the face of tragedy and to always put things into proper perspective. The general public saw the fiery militant, the biting journalist, the cultured intellectual. But beyond that Jean was a great storyteller, a fascinating and funny companion.

Did you at all time, share the views and approaches of your husband?

Jean and I certainly shared the same views. We discussed national and international politics, our work, the newsroom, and his editorials on a daily basis and we deeply respected and trusted each other. I cannot remember a major disagreement in the 28 years we lived and worked together. We also had a common approach to our profession as journalists. Our strategies might have been different at times, as we do have very different personalities. Sometimes Jean would react more aggressively than I would. Sometimes those close to him would not immediately understand his moments of “sacred anger” as we called them, but Jean was a man of extraordinary vision and with a unique sense of perspectives. The principles that guided his life were of steel. Very often I realized in hindsight that his gut feelings on a number of issues were the right ones.

Is Jean's assassination an indication that the system won't tolerate dissent in Haiti?

It is obvious that true independence of thoughts and spirit is rarely tolerated in Haiti. In Jean's case it was not only his critical attitude towards the different governments and politicians of Haiti but also his independence towards the traditional business elite. It is important to note also the increasing climate of intolerance and impunity that, in the last few years, has created in Haiti the conditions for Jean's assassination.

Richard Brisson, Manno Chalmay, Marco, vaudou beats... Radio Haiti Inter had gained a reputation of welcoming militant artists, voices and repressed musical and religious beats. Can you tell us more about Haiti Inter's contribution to the development of alternative art styles in Haiti? Can you recall some of the artists who started with Radio Haiti Inter?

Jean's decision to use Radio Haiti as a tool to lift the taboo that existed in the Haitian media, towards our own identity has certainly been a determining factor for a number of artists in the late seventies. The stress put on two determining elements of that Haitian identity, a language, Creole and a religion, voodoo has helped to free the creativity of quite a few artists, in music, literature and the visual arts. You mention our poet and comedian Richard Brisson who was the soul of Radio Haiti before 1980, Manno and Marco who were given their first chance at the station but so many other talents were revealed through Radio Haiti: I can think of a great Haitian writer, Franketienne, who wrote his first Creole novel Dezafi with Jean's encouragement. I can think of Rosemary Desruisseau whose best paintings are inspired by voodoo cosmogony. I can think of so many troubadours to whom Radio Haiti offered its microphones throughout the years, more recently, Abnor, Samba Zao or ti Koka. Jean produced Jacques Roumain's Gouverneurs de la Rosee in Creole, as well as original scripts on our history. It is also noteworthy to underline that Jean was the first to bridge the gap between artists from the Diaspora and Haiti. At the time when the “babouket” hampered freedom of speech in Haiti under Duvalier, Jean used the works of militant Haitian songwriters in the Diaspora to open our own space inside.

How is your relationship with former Haiti Inter staff? The Lilianne, Marvel, Philo…

You know, there have been quite a few journalists to have gone through Radio Haiti , in the last thirty years. Marcus Garcia now has his own Radio station. So do Liliane, Marvel and Sony. So did Fritzson Orius whose Radio station in St Marc was recently destroyed. Others have left radio all together and have chosen different paths. I am very close to the team I have been working with, at Radio Haiti, since 1991: Pierre Emmanuel, our Chief editor, and Gregory Casimir who are now in Montreal, Jean Roland Chery, Immacula Placide, Guerlande Eloi, who are in exile in the US, Paul Dubois, Sony Esteus, Francisco Augustin, Dafus Richard, Jean Robert Delciné, Julie St Fleur and others now in Haiti. I will never forget their unwavering solidarity when Jean was killed. One week after the whole team had gone to accompany Jean's ashes to the Artibonite, we sat for the first time in our newsroom. Gigi Dominique, Jean's daughter, the station's Executive Director since 1994, and I, asked them if they felt they could continue. The answer was unanimous. I still remember Gregory Casimir's reaction that day “Michele, you had the courage to cross the courtyard where Jean was killed. You are the captain of the team, we are behind you”. And they were. They took turns facing me every day across the studio glass window, so I would not be alone when I would start Interactualités in the morning. It took a great deal of courage on their part to continue working in the face of constant threats and dangers. They are a remarkable team and without their support we could not have gone as far as we went.

In numerous documentaries, Jean denounced drug trafficking, extra judiciary procedures, governmental corruption, and mismanagement of funds… Did Jean's documentaries contribute to undermine the lavalas regime?

As you know, Jean strongly supported Jean Bertrand Aristide in 1990. But to him, there were a number of principles that the democratic movement had fought for since 1986 that could not be compromised and he felt that the government that had emerged from the popular vote had to be held to the highest standards of accountability. It became obvious to him that the Fanmi lavalas regime was drifting away from these standards, towards corruption, the denial of justice and the same personality cult we had fought against. I think Jean might have seen much earlier what we realized later on, after his assassination.

Could you update the readers on efforts, local and international, to bring Jean's murder to justice?

In Haiti, during an investigation that lasted more than two years, witnesses disappeared, suspects died in jail, judges were threatened, forced into exile or had to resign. After more than a dozen indictments, the fourth instructing judge issued an “ordonnance”, a final investigation report that only accused the presumed trigger-men and none of those who ordered or paid for the crime.

That doctored report was published in March 2003, a month after Radio Haiti who had been demanding justice on a daily basis and denouncing the obstacles to the truth at all level of the power structure was forced into silence. This was less than three months after the Christmas day assassination attempt on me that costs us the life of a brave young security guard, Maxime Seide.

On April 3 rd 2003 , the third anniversary of Jean's murder, our family and Radio Haiti appealed that decision as we would not accept any criminal trial on such erroneous basis. We won. On August 4, the appellate court rejected the “ordonnance' and ordered a new investigation so as to determine who had ordered and paid for the crime.

However the decision by the appellate court to keep 3 of the 6 people formerly accused of the crime in jail until further investigation, was brought to the Supreme Court by the counsel of the accused.

Now 8 months later, the Supreme Court, has not taken any decision on the case, blocking in effect any further investigation.

In the meantime, the three accused escaped from jail a few weeks ago, as did all the prisoners in the Penitencier National.

In early March, a few days ago, the Haitian police arrested Port au Prince former deputy mayor, Harold Severe, a member of President Aristide's cabinet, as well as Rouspide Petion, alias Douze for their alleged involvement in the murder of Jean Dominique. Harold Severe had been indicted on January 28, 2003 by instructing judge Bernard St Vil but his name was, at the last minute, taken out of the judge's final report.

We have so far concentrated our efforts on the Haitian judiciary as we feel that it is important that Jean finds justice in his country. For so many who have felt that a fair trial in Jean's murder would be the key to justice for score of other less known victims, this case is emblematic. We want to use it to push the system to its limits, and force it to finally function. Few political killings have survived the test of time and the climate of increasing impunity. This one has. I think Jean would have wanted his murder to be useful in that way to others. We are fully aware of the many flaws in the Haitian judicial system but we will continue to push forward. We are at the same time, reserving our right to go to an International Court , if necessary.

Outside Haiti, we have had incredible allies in the International press, Human Rights and professional organizations, like the Committee to Protect Journalists or Reporters without Borders. They have made of Jean's case a yardstick to judge our fledging democracy. And we have today the support of a famous film maker, also a warm and considerate friend, Jonathan Demme. His film, the Agronomist about Jean's dreams and his struggle, that of the Haitian people for a democratic society and a free press, has been acclaimed in several films Festivals, from Venice to Chicago. It is opening in movie theaters on March 31 in Paris to extremely positive reviews. It is opening in New York, Los Angeles and several US cities starting on April 23 rd. It is for us a unique way to take Jean's case to a unique Court, that of International public opinion.

You have experienced two exiles, you have lived through assassination attempts, and you have seen your country stereotyped –AIDS, boat people- your husband died, assassinated. Now we have foreign troops on the land in 2004. How relevant is the notion of patriotism to you personally for the bicentennial of Haiti 's independence?

It is still relevant on a personal level, in the sense that I am Haitian and I feel I belong nowhere else. It is a deep seated feeling but an increasingly painful one, as it goes now with a profound sense of failure. We are celebrating that bicentennial with foreign troops on our soil, and the international label of a failed state. When you are forced to face the negative images of violence, and misery conveyed by the international media, it is difficult to find reasons to believe that we can rebuild Haiti as a strong, democratic nation. Can we put the weapons aside - “mettre les armes au vestiaire, toutes les armes” had said Jean in an editorial - ? Can we end the state of impunity that has denied the most basic demands for justice, with thugs now freely ruling so many of our towns and villages, prisons emptied and a paralyzed judiciary? Can we return basic ethical norms to governance, and control corruption? Can we save a land that is on the verge of ecological disaster? However, in spite of my own anguish, patriotism for me is still meaningful when I think of the incredible strength to survive of our rice farmers, our coffee growers, and our Madan Sarah.

How did Jonathan Demme come to be interested to Jean's story?

Jonathan Demme had interviewed Jean before, in Haiti. They met often during our second exile in New York. Demme wanted first to do a film about a journalist returning from exile in 94. He had several hours of interviews with Jean about Haitian politics, arts, history. In 94, the project could never be finished as Jean was too busy putting Radio Haiti back on the air. After Jean's murder, Jonathan came down to film our reopening on May 3, 2000 and had been working since on that documentary which was shaped at first as a sensitive homage to a friend, before it became a political film about a man's and a people's fight for democracy.

The funeral scene in the “The Agronomist” felt surrealistic: thousand of peasants dressed in white, the spreading of his ashes in the Artibonite River , the profound silence. What was the symbolism behind this and what was Jean's connection to the peasants of Haiti ?

Jean before he became journalist worked as an Agronomist, hence the title of Demme's documentary. He was very involved, particularly in the last two years of his life, with peasant associations. Participation of the majority of Haitians to the public life of our country was something he deeply believed in.

Radio Haiti had always worked in bringing the “peyi an deyó”, the Haitian peasantry to the forefront. I think in that sense our media have always been rather unique. A story that took place outside of “the Republic of Port au Prince” was often for us a front page story. We had a number of in-depth and feature stories about farmers and issues affecting their lives. Jean had also been personally and politically involved in the demands for land reform to empower the landless.

When Jean was killed, it was a terrible blow to thousands of peasants. When they asked me if Jean could stay close to them, our daughters and I accepted immediately, and Jean's ashes were scattered in the River, as a fertilizer to the land he loved. As they say now in the Artibonite, “Jean is alive in every grain of rice”. Jean was a free man. I could not imagine him cooped up in a traditional coffin.

The fear, the loneliness, the frequent exile, the displacement, and the threats, the stalking… As a person and as a woman, how did you cope with all of this?

It has been very difficult.

What is your sense of the recent events in Haiti that saw the departure of Aristide from power and the creation of a new government?

I am very concerned about the continuing violence, the pervasive impunity and the apparent lack of basic norms. No serious disarmament has taken place so far, in spite of promises made by the Interim government or by US and French command. Convicted criminals are not only roaming around freely, some rule a number of towns. Retaliation against members of the Lavalas party, has forced many local elected officials who were never involved in violence or corruption to go into hiding. I am afraid that with the political pendulum swinging towards more conservative forces, the legitimate demands of the majority of Haitians for basic services, for land, for justice, might be put on the back burner. The task is mind boggling. To get any legitimacy, the new government will have to send strong signals against impunity, and corruption, get institutions like public administration or the police on a national and local level to function and respond to the population basic needs before we jump once more into elections. It is going to be extremely difficult to establish order, the rule of law and reconcile our torn nation with itself.

Is Radio Haiti Inter over? What does it take to revive it, to revive its concept?

The answer is an emphatic NO. Radio Haiti is not over. More than any media, we have been harshly struck, faced death, forced to close at least seven times, gone into exile, been shot at or sabotaged. But every time we have bounced back.

It is not going to be easy to return to the airwaves. We have tremendous support, but powerful enemies. When we put the Station on the silent mode, a year ago, it was to protect the lives of our staff. Reopening Radio Haiti would now be suicidal as those who forced us to close are circulating freely. Some are even vying for a share of the political pie and would do everything they can to stop the truth. But we will return when the conditions allow us to start over. As we sing on our airwaves, “nou balance nou pa tonbe”.

Mèsi Michele

The agronomist

|

The latest work by the Academy Award-winning director of SILENCE OF THE LAMBS and PHILADELPHIA, Jonathan Demme, THE AGRONOMIST tells the story of Haitian national hero, journalist, and freedom fighter Jean Dominique, whom Demme first met and filmed in 1986. As owner and operator of his nation's oldest and only free radio station, Dominique was frequently at odds with his country's various repressive governments and spent much of the 80's and early 90's in exile in New York, where Demme continued to interview him over the years. Dominique fought tirelessly against his country's overwhelming injustice, oppression, and poverty but it was Dominique's shocking and still-unsolved assassination in April of 2000 that gave the director the impetus to assemble more than a decade's worth of material into a celebration of this dynamic man and his legacy.

THE AGRONOMIST, a portrait of a remarkable man, his extraordinary wife, and their beloved nation is being released at a time when Haiti is in turmoil. Headlines in our newspapers talk about a "cannibal army," about an upper class "revolutionary" opposition, about a compromised President who was formally a priest, and about a two-hundred year struggle for democracy. All of which brings Haiti to people's attention and may, simultaneously, confuse them.

"The Agronomist" provides what amounts to a key to make sense of this news. One of the film's major accomplishments is to provide viewers with a context in which to understand what's happening in Haiti today -- and what may happen tomorrow. Through the lives of Jean Dominique and Michèle Montas, we get to see behind the headlines and into the history that has led to today's events. Perhaps most telling to North

American viewers, "The Agronomist" illuminates the role that the United States has played in this small country's struggles -- and the influence it continues to have through its actions and/or inactions.

Finally, the greatest contribution "The Agronomist" offers is to make burningly, tragically clear the need for an objective press. Haitians and Americans are united in not being able to understand the current political situation unless we have access to accurate, unbiased information. "The Agronomist" contains the moving story of how crucial such information is -- and how much it can cost. Unfortunately, it isn't surprising that "The Agronomist" is being released at such a turbulent time in Haiti . But current events do underline the importance of the story that the film tells.