| Kaz | Enfo | Ayiti | Litérati | KAPES | Kont | Fowòm | Lyannaj | Pwèm | Plan |

| Accueil | Actualité | Haïti | Bibliographie | CAPES | Contes | Forum | Liens | Poèmes | Sommaire |

|

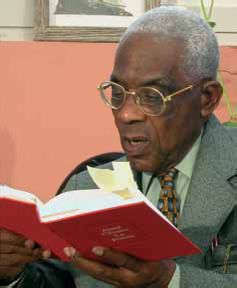

Aimé CÉSAIRE Avril 2009 Translated in English by Joelle Constant

|

|

The highest voices from around the world have come to be heard: Aime Cesaire is dead, May Cesaire live! In fact, Aime Cesaire, from his full name Aime Fernand David Cesaire, born June 26, 1913 in Basse-Pointe (Martinique), died on April 17, 2008 in the morning at the CHU Pierre Zobda Quitman of Fort-de-France. Grandson of the first black Teacher in Martinique, Son of a Controller of the Contributions, he was beneficiary of a scholarship at the Lycee Victor Schoelcher at Fort-the-France, and later (1931), fellow of the French Government for the Lycee Louis-Le-Grand where he met the Poet Leopold Sedar Senghor, one of the instigators of the Negritude movement, the other fellow whom he will bind friendship with until the death of this last. In September 1934, Cesaire, founded, in contact with friends like Leon Gontran Damas and some students from the Caribbean, Guyana and Africa (Guy Tirolien, Birago Diop and Leopold Sedar Senghor), a newspaper called The Black Student, where appeared for the first time the term "Negritude". This concept, designed by Aime Cesaire, according to Frantz Fanon, 1 is shrunk, that is, must be obsolete in response to France project, namely, cultural assimilation by the Black Man’s profound alienation. It meant, for these young students, that they would refuse any form of cultural oppression and promote Africa and its culture, always undervalued by the superiority of the White Man who is the product of this era’s colonialist ideology. The Negritude project, which is more cultural than political, was more than necessary insofar as it would have helped the Black Man to transcend the world follower and racial vision. In 1935, Cesaire enrolled to the Superior Normal School. And during that same Summer, in Dalmatia, at his friend’s Petar Guberina, he began the writing of a notebook of a return to the homeland (Cahier d’un retour au pays natal), which he completed in 1938. The title of his thesis for his graduation in the same year from the Normal School: The theme of the South in black American literature of the USA (Le thème du Sud dans la littérature noire-américaine des USA). He read the master work of Frobenius on African civilization2 in 1936. Cesaire returned permanently in 1939 in the country, i.e. in Martinique, to teach at the Lycee Schoelcher together with his Wife.

AT THE CULTURAL, POLITICAL AND RACIAL LEVELS

As it has been the case in Haiti at this distant era of the American Occupation (1915-1934), Martinique situation was to copy the Metropole, alienation which raised the problem of superiority of such race or culture, forgetting that we are all different and relatively valid, depending on what corner we are positioned. The colonial system implemented by the superpower of the last century tells us strongly on the rejection of identity of the others, on the deep oppression and on the psychosis and cultural alienation as well as the assimilation as strength of conviction to everyone’s acculturation. All Africa, including Asia and the Indian American Red skins were the losers of this colonialist ideology fueling the clichés of the native in difficulty and that need taming. In matters of literature, all good references would come from Mother France and rare martinican works should be considered on a second level. This is in response to this situation of oppressed and exploited in their culture that the Poet Aime Cesaire, supported by his Wife and several other intellectuals in the region, founded in 1941 the Tropics magazine which will disappear after many difficulties for release in 1943. Not to mention the creation of SERMAC (Service Municipal d’Action Culturelle), from workshops of folk arts and of the prestigious Festival of Fort-de-France, highlighting long tapping parts of African culture.

The poetry and philosophy of Aime Cesaire have influenced thousands of intellectuals of the Third World, if not the whole world. Famous writers such as Frantz fanon and Edouard Glissant, to mention only those two – have had as their Professor of letters at the Lycee Schoelcher no one but the Poet Aime Cesaire. Even more than his presence on the Island, Martinique, is the publication of two of his dozens of books, namely his Book a Return to the Native Country (Cahier d’un retour au pays natal) (1939), and his Speech on Colonialism (Discours sur le colonialisme) (1955) which made it quite difficult for the Colon to co-habit especially in a completely paradoxical space and perspective to the original concept: Slavery. So has developed the gap between the Grandson of a former slave who became a Writer, Mayor of Fort-de-France (1945-2001) and Deputy of Martinique (1945-1993), and heir to the Creole White people, the Bekes, these monarchs who seem to still live from trafficking. Far from punishing to become the counterpart of the strong man of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, on the political plan, rather favored dialogue for his folks in and by the Art of Writing. As a parliamentary man, he worked on a daily basis to encourage the poorest of Fort-de- France and the generations of peasants who have been chased out at the end of the Sugar Housing, by his municipal actions, such as buildings, in place of cesspools and the slums, true livable neighborhoods, with their schools, district roads, clinics, water, electricity, creating some kind of dignity.

If World War II (1939-1945) had put a flat at the launch and recognition of Martinique on the world map under the regime of Vichy (blocked by the USA), the work and the fame of one of his Sons, Aime Cesaire, have accelerated the arrival in Martinique, of the Pope of the Surrealists Andre Breton, who had discovered the Notebook of a return to the homeland (le Cahier d’un retour au pays natal) in France and met Cesaire in 1941. This led to the forewords of Breton to the bilingual edition of the Notebook of a return to the homeland (le Cahier d’un retour au pays natal), published in the Fontaine Magazine, Issue 35, directed by Max-Pol Fouchet, as well as the book Miraculous Weapons (Les armes miraculeuses) in 1944.

PLACE HABITED: BIRTH OF A POETRY

Praising the refinement of a culture more than another in this mosaic of peoples and tribes of Africa, the Caribbean or Asia, is something of atypical resonance. And how can we understand that the inhabited place should belong to others, wouldn't it be by way of an unhealthy aggression in the name of the superiority of the race? Of the race in America. Cesaire replied: "I am of the race of those that are oppressed."

Aime Cesaire, fleeing racial discrimination at the time of his studies in France, is part of these writers of the 1940s-50s who gave a new breath to African, American and Caribbean literature, once returned to the country. This tradition of "transfer of energies on a new space" known long time ago in Europe or America, has also, by force of historical and political events, been introduced in the life of the Caribbean writer. Indeed, since Cesaire, everyone can notice that the vast majority of Caribbean writers leave their country to be better equipped with new ideas and go back later. Expatriation, as well as tenacity in the art of Writing, has quickly become the only remedy to the Caribbean writer conscious even today, of the difficulties of identity and the ailments of the black man.

Aime Cesaire, to our knowledge, has published seven books of poetry: Notebook of a return to the homeland (Cahier d’un retour au pays natal) (1939, 1947, 1956), miraculous weapons (Les armes miraculeuses) (1946 and 1970), Cut neck Sun (Soleil cou coupé) (1947 and 1948), Lost body (Corps perdu) (1950), Fittings (Ferrements) (1960 and 1991), Cadastre (Cadastre) (1961), Me, laminar (Moi, laminaire ) (1982); four essays: Slavery and colonization (Esclavage et colonisation) (1948), Victor Schoelcher and the abolition of slavery (Victor Schoelcher et l’abolition de l’esclavage) (2004), Speech on colonialism (Discours sur le colonialisme) (1950, 1955, and 1989) Speech on Negritude, (Discours sur la négritude ) Paris (1987-2004); four plays for theater: And the dogs shut up (Et les chiens se taisaient ) (1958 and 1997),The tragedy of King Christopher (La tragédie du roi Christophe) (1963 and 1993), One Season in Congo (Une saison au Congo) (1966 and 2001), A storm (Une tempête) (1969 and 1997); A book on Haiti: Toussaint Louverture, the French Revolution and the colonial problem (Toussaint Louverture, la Révolution Française et le problème colonial) (1962); and two books of interviews: Meeting with a fundamental Negro (Rencontre avec un nègre fondamental), Dialogue with Patrice Louis (2004); A Negro I am, A Negro I will remain (Nègre je suis, nègre je resterai), Dialogue with Françoise Vergès (2005).

The poetic work of Aime Cesaire has been much analyzed especially in Europe, in the Caribbean, in Africa and South America by students and professors raftered in conferences and congress, public conferences, among all. In addition to many studies on his poetry, more than one hundred of articles of literary, sociological and political nature have been published on his theater and his writings. Moreover, his speeches, particularly those on colonialism and negritude, were revisited by several researchers of the whole world. With the counting3 until now, more than thirty monographs, theses, collective works and conference works were carried out on his behalf. Of course, of many international symposiums were devoted to him in various places: McGill University (Montreal), University of Montreal (Montreal), Queen's University (Kingston, Ontario), in Paris, in Guyana, in Bamako (Africa), in Fort-de-France, in Germany, in Haiti, in Guadeloupe and in Switzerland.

Raphael Confiant4, one of the literary heirs of Cesaire, in a moment of extreme confidence, exclaimed somewhere: “I will retain, finally, the immense melancholy, rarely underlined, which crosses his so brilliant poetic work. A deaf and tough melancholy, rarely underlined, which never outcrops on the first level, which never forces him to lower the arms and to cease acting, but which is there, omnipresent and which reveals us a man worried by the destiny of his people or his race, but wondering at same time about the true meaning of the human existence.” This sentence, in its entire splendor, bewitched us and even forced to seek this extreme melancholy which rises from the work of the fundamental Negro.

For emotional reasons, we will approach only the poetic work of Aime Cesaire, which, already very studied by critic 3, pushes us to visit it only on the psychological level of the melancholy. We will thus be contented to analyze his poetry only through a published retrospective of all his poems5.

From his first till his last work published, Me, Laminar, (Moi, Laminaire), in 1982, the melancholy which is a source of suffering not of environment, of regrets and not of adjustments, of sobs and not of laughs, is found in the claims of the poet in his timetable and memory, in the field of the possibilities of a better world. May one judge some:

“My mouth will be the mouth of misfortunes which do not have a mouth, my voice, the freedom of those which subside with the dungeon of despair.”

(Book of a return to the homeland)

“I live a crowned wound

I live imaginary ancestors

I live a shadowed desire

I live a long silence

I live an irremediable thirst

I live a trip of a thousand years

I live a three hundred year old war

I live an unused worship….

(Me, Laminar)

A whole melancholy which is displayed, of course, in the indifference and the whole incomprehension of those who are concerned. Freud would say, differentiating the mourning of melancholy, that the latter is latent, multiform and chronic, whereas mourning is sanguinary but momentary. It is from this definition that one may understand the burning sob of Cesaire, the poet, for his people and for humanity.

“… I would be a Jewish

an Kaffir man

a Hindu-of-Calcutta

a man-of-Harlem-which-does-not-vote

a man-famine, a man-insult, a man-torture…”

(Book of a return to the homeland)“… for my dream with the legs of late watch

for my hate of cast cargo…”

(Miraculous weapons)

This voice which expressed in the most beautiful and strongest way the sufferings, not only of the black people, but also of all the oppressed people on earth, of all those that colonization, then the imperialism threw in the hecatomb of despair and oblivion, of self-denial, this voice has not always been understood by his own brothers, the poets. Anyway! In a cry of superb challenge, by pushing “the great negro cry which will shake the world bases”, this man, this poet set in motion generations of writers and thinkers which will have had the role to transcend centuries of denigration of the colored man and, at the same time, to rehabilitate the Alma Mater: Africa. Then, Edouard Glissant and his “Antillanity”6 thereafter came: Chamoiseau, Bernabe and Confiant and their “Creolity”4, yet in Martinique. All this therefore explains the need and the importance of the Negritude movement at the last century. The poems of Cesaire and a good number of other poets of this era have obviously caused a true psychoanalysis of the neuroses (or psychological disorders) that colonization and its attributes had generated and perpetuated in the Caribbean writers and the whole colored persons.

The melancholy of Cesaire is an expressive reaction of which it is important to consider polysemy, meaning, the source of the approximations and interrogations, i.e., the identity complex or the totalitarian dispute related to it. This is certain when we think of the existential adventures of the black people at the time of slavery, and especially, of the crossings generated in the marginality of the cultures in filiations with the protagonists. More than the melancholy, the language used is livable, inhabited by the violence of the Verb, and by disputes of all kinds. This process of cultural assignment needs to be sincere insofar as the sum of the admonishments of the Negro requires a statute of a free writer and indissoluble to his pairs. One must question this statute insofar as the difference between the black and the white man is developed, between two races of society cohabitation, two entities which made humanity progress.

“Who and which we are? Admirable question!

Hatreds. Builders. Traitors. Hougans. Especially Hougans.

Because we want all the demons

Those of yesterday, those of today

Those of the yoke, those of the hoe

Those of banning, prohibition, marronnage

and we do not have the right to forget those of the slave trader…

Thus we sing.”

(Book of a return to the homeland)

“Freedom my only pirate, water of the new year my only thirst

love my only sampan…”

(Miraculous weapons)

TO DOMICILE AFRICA IN WEST INDIES

Again, because of this melancholy, this wounded man was in search of an imaginary fatherland, it seems. He wanted to install in each West-Indian the conscience of Africa, the knowledge and the recognition of this continent in the interstices of the black Man and the Third World. Fanon1 wanted that it goes further in spite of the disagreements of this period of time by denying the occult forces which could act, leading for example to the death of Patrice Lumumba. But what does it mean for him, for Cesaire, the act of indicating the words against the existence of an infallible system at that time? Without him, Senghor, Dubois7 and consorts, there would not be this America which one currently knows, the America of Mr. Barack Obama8. Let us listen to him describing a part of this continent:

“At the end of the small hour budding of frail handles, the Caribbean which are hungry, the Caribbean hailed of small pox, the Caribbean dynamited of alcohol, failed in the mud of this bay, in the dust of this city sinisterly failed.”

(Book of a return to the homeland)

One could not help to dislike his geographic origin, his place of belonging, his native tongue, his morphological difference, his birthplace, and even his cultural and pathetic cartography. Cesaire insists, with reason, on the active part which the writing a poem consists of, and to some extent, the engagement of the poem and the poet to a cause.

“Thus, our hell will take to you by the collar.

Our hell will make your thin skeleton bend.”

“You

O you who are blocking your ears

it is to you, it is for you that I am speaking, for you…”

(Book of a return to the homeland)

Yet, the melancholy of disengagement? Yet an organized sadness, but denounced by the creative activity. Yet, God who shines by his absence.

“It is me, only me

who snogs with the last anguish…”

(Book of a return to the homeland)

“But God? how could I forget God?

I mean, Freedom…”

(Miraculous weapons)

There is no secrecy for anybody that we, the Negros, have built with our bad sweats this America, and that we are therefore part of humanity, seems to shout the poet:

“Haiti where negritude stood up for the first time….

And I say myself Bordeaux and Nantes and Liverpool

and New York and San Francisco

not a piece of this world which does not carry

my digital fingerprint

and my calcaneum on the back of the skyscrapers

and my dirt in the flutter of the gems! ”

(Book of a return to the homeland)

Of sadness and an extreme melancholy, we repeat, this writing does not remain therefore circumscribed to only one case of literary figure. Far from us the idea of the refusal of the community of the African or West-Indian literary which suffer or have suffered from the same sadness and all the melancholies associated with these segments with the History. For Cesaire, the melancholy so far from being morbid, expresses the pulsation of the collective, a collective in the search of an imaginary function, being the equality of the races and the symbiotic belonging of the great flood of people. Cesaire, indeed, in his speeches, wanted to finish with the social and racial problems at the harm of the colonial enterprises. Nevertheless, it is more than certain that this poetry was born in a context of clannishness, garrison and explosion spirit. This would explain his characteristics of presence in life, of recourse to dispute and subversion. This mentality, this “spirit of garrison”, according to the word of Northrop Frye9, did not at all block the poetic writing of a great poet like Cesaire. Jean-Paul Sartre, together with Breton, not being blind at the point to refuse any social improvement of this race, have preferred to live with, and have chosen to strongly greet it with the contempt of colonial mentality.

If one of the roles of the literature is to fail chaos, the poet Cesaire, by choosing this cause, which is literature, his race and humanity, has been able to reinforce the existing bond between literature and people, this correlation of the reception by means of the writing of the poem. It is in space that the poem has the capacity to connect all; to restore man creation; to join together all that is contrary to humanity, the poet being himself a parallel presence and a poetic synesthesy, absence of concretization on the cover of the opposites and the simultaneous confrontations. The multitude, the search of negro space, the existential and racial anguish, arise as the triptych of this long walk towards the vast unit which is freedom, an almost obsessional need for the poet. Cesaire, the fundamental negro, put all himself on the paternity of the words since it is his natural principle. Principle which accompanies the plurality of the metaphors or the hidden dynamism of his work, crossroads of aspirations and self-accomplishment of the human being.

Not

- Frantz Fanon, Black skin, white masks, Paris, Maspero, 1952; The Damned of the earth, Paris, Maspero, 1961; For African revolution, Maspero, 1964. The foreword of Jean-Paul Sartre for The damned of the earth, as well as the Anthology of the new Negro and Madagascan poetry of Senghor, was obviously the kickoff (or the grace signal) for the anti-colonialist fight and the emancipation of the Third-world, and especially for the consecration of the Negritude movement.

- Léo Frobenius, History of African civilization, Paris, Gallimard, 1933.

- Bernadette Cailler, Poetic proposal - A reading of the work of Aime Cesaire, Sherbrooke (Québec), Naaman, 1976; Paris, News of the South, 2000; Lilyan Kesteloot, Aime Cesaire, Paris, Seghers, 1979; Clément Mbom, The Theater of Aime Cesaire or the primacy of human universality, Paris, Nathan, 1979; Marcien Towa, Poetry of Negritude – Structuralist Approch, Sherbrooke, Naaman, 1983; Aliko Songolo, Aime Cesaire – A poetics of discovery, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1985; Albert Owusu-Sarpong, The historical time in the theatrical work of Aime Cesaire, Sherbrooke, Naaman, 1986; Paris, L’Harmattan, 2002; Collective, Aime Cesaire or the Athanor of an alchimist – Acts of the first international symposium on the literary work Acts of the first international symposium on the literary work of Aime Cesaire, Paris, November 21-23, 1985, Paris, Caribbean Editions, 1987; Gloria Nne Onyeoziri, The poetic word of Aime Cesaire – Essay of literary semantics, Paris, The Harmattan, 1992; Victor M. Hountondji, The Notebook of Aime Cesaire. Literary elements and factors of revolution, Paris, The Harmattan, 1993; Gilles Carpentier, Letters to Aime Cesaire, Paris, Seuil, 1994; Georges Ngal, Aime Cesaire, a man looking for a homeland, Paris, African Presence, 1994; Roger Toumson and Simone Henry-Valmore, Aime Cesaire, the unconsoled Nigger, Paris, Syros, 1994; Michael E. Horn, The multi-vocalism in «Notebook of a return to a homeland» of Aime Cesaire, Doctorate Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, 1999; Rene Henane, Aime Cesaire, The injured song - Biology and Poetics, Paris, Jean-Michel Place, 2000; Tshitenge Lubabu Muitibile K. (éd.), Cesaire and Us. A meeting between Africa and the Americas in the Twenty-First Century, Bamako, Cauris Éditions, 2004; David Alliot, Aime Cesaire, the universal Negro, Gollion (Switzerland), Infolio, 2008.

- Co-author with Patrick Chamoiseau and Jean Bernabe de Praise of creolity, Paris, Gallimard, 1989. Has published on Cesaire : Aime Cesaire. A paradoxical crossing of the Century, Paris, Stock, 1994.

- Aime Cesaire, Poetry, Paris, Seuil, 2006.

- Edouard Glissant, The West Indian Speech, Paris, Seuil, 1981; re-editing: Gallimard, 1997.

- William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, Black Souls, Paris, African Presence, 1903.

- Barack Obama, Of the race in America, Paris, Grasset, 2008.

- Northrop Frye, Anatomy of criticism, Paris, Gallimard, 1969.

Well-known work of Aime CESAIRE:

Retrospectives

- Complete Works (Oeuvres complètes) (Three books), Fort-de-France, Desormeaux, 1976.

Poetry

- Notebook of a return to the homeland (Cahier d’un retour au pays natal), in the magazine Volontés, Paris, no 20, 1939; Paris, Pierre Bordas, 1947; Paris, African Presence, 1956.

- The miraculous weapons (Les armes miraculeuses), Paris, Gallimard, 1946 and 1970.

- Cut neck Sun (Soleil cou coupé), Paris, Editions K., 1947 and 1948.

- Lost Body (Corps perdu), Paris, Fragrance, 1950.

- Fittings (Ferrements), Paris, Seuil, 1960 and 1991.

- Cadastre (Cadastre), Paris, Seuil, 1961.

- Me, Laminar (Moi, laminaire), Paris, Seuil, 1982.

- Cadastre (Cadastre) (followed by) Me Laminar, Paris, Seuil, 2006.

- Poetry, Paris, Seuil, 1994 and 2006.

-

Essays

- Slavery and Colonisation (Esclavage et colonisation), Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1948 ; Re-edition : Victor Schoelcher and the abolition of slavery (l’abolition de l’esclavage), Lectoure, Le Capucin, 2004.

- Speech on colonialism (Discours sur le colonialisme), Paris, Réclames, 1950 ; Paris, African Presence, 1955 and 1989.

- Speech on Negritude (Discours sur la négritude), Paris, African Presence, 1987 and 2004.

Theater

- And the dogs shut up (Et les chiens se taisaient), Paris, African Presence, 1958 and 1997.

- The tragedy of King Christopher (La tragédie du roi Christophe), Paris, African Presence, 1963 and 1993.

- A Season in Congo (Une saison au Congo), Paris, Seuil, 1966 and 2001.

- A storm (Une tempête), Paris, Seuil, 1969 and 1997.

History

- Toussaint Louverture, The French Revolution and the Colonial problem (la Révolution Française et le problème colonial), Paris, African Presence, 1962.

Dialogues

- Meeting with a fundamental Negro (Rencontre avec un nègre fondamental) (Dialogue with Patrice Louis), Paris, Arléa, 2004.

- A Negro I am, a Negro I will remain (Nègre je suis, nègre je resterai) (Dialogue with Françoise Vergès), Paris, Albin Michel, 2005.