| Kaz | Enfo | Ayiti | Litérati | KAPES | Kont | Fowòm | Lyannaj | Pwèm | Plan |

| Accueil | Actualité | Haïti | Bibliographie | CAPES | Contes | Forum | Liens | Poèmes | Sommaire |

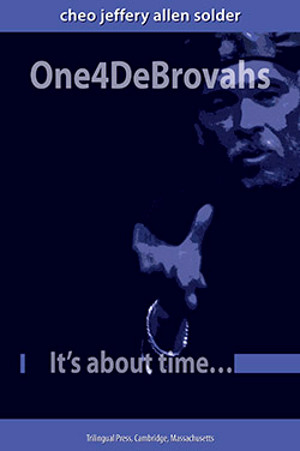

One4theBrovahs Cheo Jeffery Allen Solder

One4theBrovahs, Cheo Jeffery Allen Solder • 2014 • |

|

Voice of a Brother: One4theBrovahs, the book of Cheo Jeffery Allen Solder

Trilingual Press is proud to announce the release of One4DeBrovahs, a critical collection of memoirs by Cheo Jeffery Allen Solder.

The reader will be taken aback, first of all, upon seeing the liberty with which Cheo Solder utilizes the English language, as both a street-savvy African American intellectual, and a musician turned memoirist. His is the kind of thought you may have if you have been in a certain place, encountered certain people, and lived certain lives. Or simply the life of a Brovah.

It took this writer a while to get past the all-lower-case alphabet the author adopts and uses in the entire book. As soon as this bridge is crossed, however, the reader is led to a flow of linguistic adventure and analytical daring such as one finds in poet-thinkers like Langston Hughes and Amiri Baraka, two icons of African American letters. The resemblance to Baraka is not at all surprising, given that the late iconic writer was the one who dubbed Solder with the nickname Cheo.

Reading Cheo Solder’s foray into the frontier of language and memory—memory that shapes and strengthens at the same time the constitution of both the living author and the text—one comes out refreshed, even enlightened. If you can conciliate the more pious-sounding turns of phrase with the take-no-prisoners narrative the author clearly relishes, you will appreciate his well-tempered analysis of the power politics of the United States and its devastating impact on the most vulnerable of its populations.

Solder’s personal story—if we assume a first-person narrative is necessarily about an author’s own experience—adds a certain poignancy to the narrative. His writing, while personal on many levels, is also a connection to others’ suffering, in the sense that his personal experience reflects the general process of learning, of apprehending, the universal process of political conscientization in a situation of oppression.

One of the author’s rebellious acts of writing was when he wrote a letter to the US draft board during the Vietnam War outlining the reasons why he should be exempted:

“…i avoided serving there by writing a letter that took me almost six months to compose. I wrote to the draft board that i was not interested in helping white men murder people of color for whatever was the current reason. i wrote about history. i wrote about the real reason they were so interested in this far off piece of the world. naturally there was something there that the white man wanted and in this case it had to do with minerals and ore, tungsten being the main one in abundance, if i remember correctly. i wrote about crispus attucks and his being the first to give his life for the american revolution and i wrote about the brothers in the civil war who fought fearlessly and i wrote about the buffalo soldiers who helped subdue the red man out west and i wrote about the black men who fought in every war and then came home to be lynched and discriminated against. i wrote about the reasons why we fought and, in my opinion, the reasons why we should not have fought. i wrote about my grandfather who was in the navy for over thirty years and fought in two wars. I wrote about my father who was briefly one of the tuskegee fliers and then i wrote about myself and how i was not going to run to canada or refuse to be inducted, since i could not claim to be non-violent, though i did not want to murder anybody if i could help it.”

Indeed, the seeming dualism between liberated impulses and conformity to conventional lore is evident in the author’s treatment of religion and the acceptance of the notion of God as the creator. But to read carefully his elaboration on his conception of God, you have a sense it’s a rather naturalist, materialist, even relativist God:

“no, i say that god is everywhere, residing in every tree and blade of grass and mountain of stone and ocean deep and white of cloud and blue of sky and in the infinite stars. god is on the breeze blowing across your face as you walk. god is in the cry of a newborn babe and in the stare of the dying and the maimed by war, domestic and foreign…”

The author’s unconventional approach to writing can suddenly take a turn to classical high-mindedness and elegance as evidenced in the following paragraph:

“by this time, the sun would have long ago set and the southern california night air would carry a slight nip and sweaters would magically appear along with the lights in the backyard (we were free to go indoors but we seldom did) and the children would be sleepy and cranky after a long, hard day playing with the cousins (so many cousins it was hard to count them all but we knew them all) and then the families would go their separate ways home again, full and satisfied until the next time.”

After reading his justifications for not participating in the killing of the Vietnam War, one becomes more sympathetic to the special relation the author claims with God, an undefined God:

“the god i have come to know and trust and cherish is the property of no one religion or sect or group, no matter how hard they pray or loud they make the claim. in trying to own god, to declare that limited and puny you alone have god’s ear and heart, in trying to cut god down to size to fit into your small ornate container, your particular brand, you box yourself off from the true magnificence of god. you cut yourself off from god and you have cut off god from yourself. the wonder is lost to you because you have ceased to wonder”

The memoir centers mostly around world events, and the author has spared none of the jackals of the last forty years of US history, but his ire seems particularly severe when talking about the Bush administration and the neocons that perverted to the absurd the notion of war as the continuation of politics:

“they lied repeatedly about any and everything, even when the truth would not have hurt them. through it all, bush revealed himself to be ignorant, arrogant and lazy. cheney revealed himself to be an immoral thug and the power behind the curtain. rumsfield revealed himself to be totally dishonest. powell’s reputation was in tatters and he was scraped off like shit on the sole of a shoe. rice was the bride of the devil. rove was evil personified and wolfowitz was his brother. have i forgotten anyone?”

The most striking, poignant part of the book describes the relationship of the author with his father, which he relates in the chapter “the king is dead but not forgotten”. Solder’s parents divorced when he was one year old. “i grew up with him on the periphery,” he says.

“i remember the day he left. my brother and sister and i were in a bedroom and they were shouting and fighting out there somewhere in our little house that seemed so endlessly big to me at the time. he came into the room and kissed our crying faces and said: “i’ve got to go now. you kids be good. remember i love you.” and then he was gone. it is my earliest memory of him and is almost as painful today as it was so many years ago and it is crystal clear in my memory after all these years. i was a baby and yet i remember his words exactly. strange isn’t it?”

The father as the elusive, furtive figure certainly plays a Romantic role in the upbringing of the child, but the relationship with the mother, despite the seeming neurosis that permeates it, is perhaps the most enduring, the most determining of the two with regard to the formational development of the individual Cheo Solder, though the dominant specter of the father is never too far off. The narrator’s love for this single mother of three children is deep. You can feel it in a story he relates concerning an accidental fire he caused when he was around seven or eight years old. The mother was absent when the fire occurred and a neighbor helped put it out, but the only casualty was his mother’s bed which was burned in the fire. Fearing his mother’s ire, he stayed awake all night, awaiting her return:

“the door to my room opened and there was my mother. she did not say anything for a minute and then she came and sat down beside me. finally, after taking in my smoke stained face with the paths of shed tears coursing down my cheeks, she said; “it looks like you’ve had a long night”. i answered that this was indeed the case. she thought about that for a second and then said: “maybe we should get some sleep then”. and she lay down in my bed, pulling me with her and wrapped her arms around me and we went to sleep. she never did mention that bed. not ever. not until i was a grown man and even then i had to bring it up myself.”

One4DeBrovahs is worth the read: it’s poignant, entertaining, and also eye-opening. It is rare to have these three dimensions in one book. You may order this book on the Trilingual Press web page.

![]()