| Kaz | Enfo | Ayiti | Litérati | KAPES | Kont | Fowòm | Lyannaj | Pwèm | Plan |

| Accueil | Actualité | Haïti | Bibliographie | CAPES | Contes | Forum | Liens | Poèmes | Sommaire |

|

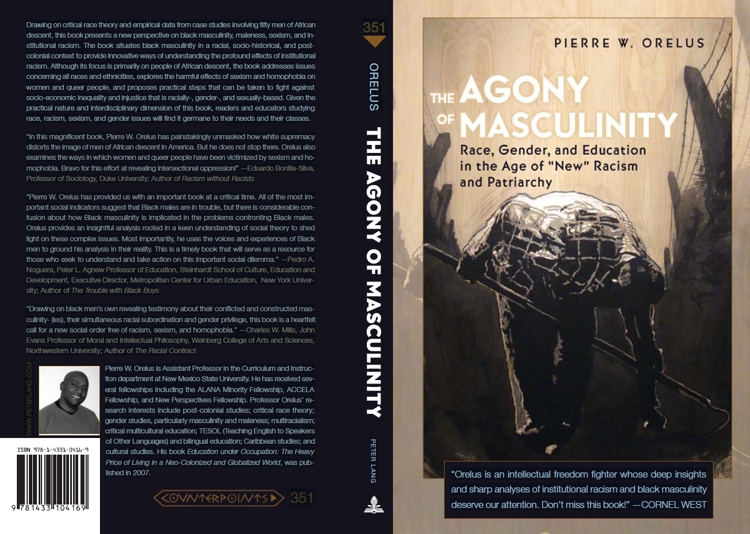

Race, Gender, and Education, Pierre W. Orelus

The Agony of Masculinity, Pierre W. Orelus • 2009 • ISBN 9781433104169 |

Drawing on critical race theory and empirical data from case studies involving fifty men of African descent, this book presents a new perspective on black masculinity, maleness, sexism, and institutional racism. The book situates black masculinity in a racial, socio-historical, and post-colonial context to provide innovative ways of understanding the profound effects of institutional racism. Although its focus is primarily on people of African descent, the book addresses issues concerning all races and ethnicities, explores the harmful effects of sexism and homophobia on women and queer people, and proposes practical steps that can be taken to fight against socio-economic inequality and injustice that is racially-, gender-, and sexually-based. Given the practical nature and interdisciplinary dimension of this book, readers and educators studying race, racism, sexism, and gender issues will find it germane to their needs and their classes.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Praise for the Book: Dr. Pierre Orelus is an intellectual freedom fighter whose deep insights and sharp analyses of institutional racism and black masculinity deserve our attention. Don't miss this book! - Cornel West

In this magnificent book, Professor Pierre Orelus has painstakingly unmasked how white supremacy distorts the image of men of African descent in America. But he does not stop there. Professor Orelus also examines the ways in which

women and queer people have been victimized by sexism and homophobia. Bravo for this effort at revealing intersectional oppression! - Eduardo

Bonilla-Silva

Pierre Orelus has provided us with an important book at a critical time. All of the most important social indicators suggest that Black males are in trouble, but there is considerable confusion about how Black masculinity is implicated in the problems confronting Black males. Orelus provides an insightful analysis rooted in a keen understanding of social theory to shed light on these complex issues. Most importantly, he uses the voices and experiences of Black men to ground his analysis in their reality. This is a timely book that will serve as a resource for those who seek to understand and take action on this important social dilemma. - Pedro A. Noguera

Drawing on black men's own revealing testimony about their conflicted and constructed masculinity (ies), their simultaneous racial subordination and gender privilege, this book is a heartfelt call for a new social order free of racism, sexism, and homophobia. - Charles Mills

![]()

![]()

![]()

|

Pierre W. Orelus is Assistant Professor in the Curriculum and Instruction department at New Mexico State University. He has received several fellowships including the ALANA Minority Fellowship, ACCELA Fellowship, and New Perspectives Fellowship. Professor Orelus' research interests include post-colonial studies; critical race theory; gender studies, particularly masculinity and maleness; multiracialism; critical multicultural education; TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) and bilingual education; Caribbean studies; and cultural studies. His book Education under Occupation: The Heavy Price of Living in a Neo-Colonized and Globalized World, was published in 2007. |

|

|

Foreword

Writing this book was the most emotionally challenging experience I could have ever had. Specifically, while writing this book I found myself personally confronting my own maleness. That is, I found myself facing regrettable, unpleasant, and hurtful things that I did to women, including those who have truly cared for me. This painful experience helped me realize how much the male behavior that I learned and the patriarchal society in which I was socialized have led me to reproduce oppressive sexist behavior and actions such as misleading and lying to women. Critically reflecting on and questioning my male privileges, I decided that I would challenge these privileges and encourage other men to do the same. Thus, I hope this book will serve as an inspiration to all men to take actions against their male privileges. I also hope that it will challenge individual whites to take a stance against institutional racism and white supremacy. Finally, it is hoped that this book would inspire heterosexual men and women to challenge their heterosexual privileges and fight against sexism, homophobia, and the oppressive nature of the patriarchal system.

The Source of Inspiration for This Study

I must make clear that the idea of writing a book about maleness in the context of men of African descent was not in the forefront of my mind, as it was not the core of my research interest. Although my interest in gender studies led me to pursue and earn an advanced graduate certificate in women studies, writing my second book on maleness in the context of men of African descent was beyond my wildest imagination. An intellectual encounter with a feminist philosopher and activist in a classroom setting made it all happen.

While taking a course on feminist theory in fall 2006 with a professor named Ann Ferguson, I told her that for her class I would like to do a research project on masculinity, which I ended up not doing. Instead, I wrote a theoretical paper on the socioeconomic conditions of “Third World” women in which I articulated how sexism, Western capitalism, and patriarchy have impacted the life of Caribbean women, particularly Haitian women. However, as I continued talking to Professor Ferguson about gender issues, she mentioned to me the name of a Caribbean student whose research interest focused on masculinity. I already knew that this student was interested in the topic but still did not feel an inner desire to explore it, beyond considering it as interesting. I also knew another Kenyan scholar/student who was and still is interested in masculinity. I interacted with him quite often while I was finishing my course work for my doctoral studies at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Both of these students have invested a lot of time and energy in exploring this topic. They both wrote and presented scholarly work at national and international conferences on masculinity. One of them, the Kenyan student, was involved in gender training in his native land and aimed to help young men develop some level of awareness about their masculinity and maleness. Through this training, he also helped these young male Kenyans realize how the performance of their maleness negatively impacted Kenyan women and themselves. Both the Caribbean and the African students showed a lot of passion while talking about this topic. I was fascinated by their passion, but such fascination was insufficient to stir in me a deep desire to explore the issue.

In addition to these two students, my partner sometimes used the word maleness when she wanted to challenge some of my male behavior. She often lamented how my maleness made it hard for her to be truly intimate with me. The maleness wall that I consciously or unconsciously used to repress my emotions and mask my inner self shadowed my life for more than two decades. The main reason was that I did not want to show my vulnerability, weaknesses, and emotions to women or men. The secondary reason was that I was afraid of questioning and challenging my own maleness, which has granted me some unearned privileges throughout my life trajectory from the Caribbean tropical island, Haiti, to the U.S imperialist land.

My struggles challenging my own maleness and masculinity helped me test and confirm a theory: challenging one’s privilege is the greatest challenge one can ever face, and the toughest decision one can ever make or the hardest task one can ever take on is to try to make one challenge his/her privilege, let alone give it up. The underlying reason for this is that privilege, be it earned or not, often leads to a sense of blind entitlement.

I used the masculinity and maleness wall for over two decades as a self-defense to survive in this patriarchal society. This wall did not shatter until I finally realized that liberation begins first and foremost with oneself and more specifically with one’s inner self. This realization led me to the road of introspection and self-questioning, which in turn challenged me to unveil the masculine and maleness mask that I had been wearing for over two decades. This then led me to explore an important issue, black masculinity, which I believe is worth examining not only for the benefits of men and women of color but also for people of other races.

In January 2008, while I was in the middle of finishing my doctoral dissertation and looking for a faculty position at some universities in the U.S., I started crafting some ideas not knowing exactly what aspects of masculinity I should focus on and explore. However, I was clear on one thing, that is, I wanted to explore some aspects of masculinity that have not been fully explored in the literature. This is how the idea of exploring masculinity in the context of men of African descent emerged and fully captured my human and intellectual imagination. This was the first but important step.

However, after deciding on the aspects of masculinity that I wanted to focus on, I was faced with the challenge of figuring out how I would materialize the conceptualization of the book. My first inclination was to write a theoretical book about masculinity based on my ideas and those of acclaimed scholars such as Michael S. Kimmel, Cornel West, bell hooks, Victor Seidler, Bob Pease, Jason Katz, and Michael Dyson, among others. But the problem that I anticipated facing was that, as I later found out, there are not many studies that link masculinity to blackness, which is the main focus of my book. Having realized this dilemma, I decided that I would interview as many men of African descent as possible in order to find out how they understand and perform their maleness in both public and private arenas and what has been their experience with racism.

The stories that the informants involved in this study shared about their life experiences illuminate how they have been taught to perform their maleness and the extent to which such performance has been harmful to women and to themselves. Their vibrant stories also illustrate how masculinity has been socially, historically, politically, and culturally constructed in a way that maintains the patriarchal system. Finally, their stories reveal how much they have suffered from institutionalized racism and white supremacy due to their racial background. In the following section, I explain what challenges I faced conducting this study and what I learned from these challenges.

Challenges Faced and Lessons Learned

I faced some terrific challenges while conducting this study. Many men of African descent involved in the study hesitated to talk about their maleness. However, they were eager to talk about blackness, which seemed to be a topic that gave them a platform to talk about their experience with racism. Because the main focus of this book was to explore masculinity in the context of men of African descent, I made sure that my discussion with them centered on this topic. At times, it was very challenging to do so, as their desire and inclination to talk about their experience with racism and white supremacy seemed stronger than that of talking about their maleness.

I therefore had to set boundaries. While doing so, however, I respectfully took into consideration various positions my informants took about their maleness and blackness. Looking back, I feel that this helped me better document and fully capture life events and/or circumstances that have shaped their masculinity and experience with racism. From their stories, I have learned that pure rhetoric or assumption about black men’s performance of maleness does not tell us much about the root causes of such performance. Many confessed that they feel that they have to perform a hyper form of masculinity so they can get respect from people. Moreover, many of the informants claimed that as men of African descent the only thing they can hold on to now is their manhood, which was stolen from their ancestors during slavery.

They also stated that they refuse to show any weakness in their male performance because they fear people would disrespect them. I argue that the vulnerable side about their manhood that these informants refused to reveal can actually teach them how to be human, compassionate, and loving. This can also be a channel through which they acknowledge their weaknesses while honoring their strengths. Moreover, many of them shared with me that they have a great relationship with their mothers, grandmothers, and sisters, and that their mothers are their queens, their role models, and their reason for being. However, the view that some of them expressed about women was disturbingly sexist and empty of human compassion.

I pointed out the contradiction imbedded in their statements. I did so because I wanted to show how the patriarchal system ideologically programmed men’s minds to denigrate women and gay men as a way to maintain the status quo. From their statements about women and gay men, I inferred that the more sexist and homophobic people are, the better it will be for the patriarchal system. This system has created, institutionalized, and inculcated homophobia and sexism in people’s consciousness. Another important thing that I inferred from the narrative of many of the informants is that the patriarchal system failed many men by inculcating into their minds that in order to be a man and be respected, they must hide their emotions, show toughness, and try to be always in control. As a black man from the Caribbean, I have also been a victim of this erroneous and destructive mindset, which I explore in depth in Chapter 1.

In part, this study allowed me to research the experience of men of African descent with their maleness and racism that is similar to mine. For this reason, I felt particularly invested in this research. Also, because of this important factor, I brought a lot of passion and energy to it. However, as a researcher, I am fully aware that my biases could impact the outcome of this research. Therefore, I analyzed my representation of the realities and struggles of the informants by doing a critical analysis of such representation. I did so by providing evidence for conclusions that I drew from their stories.

Why Write This Book?

As a heterosexual man who recognizes and challenges the unearned privileges that I have had by virtue of my gender (male) and sexual orientation (straight), I decided to write this book with the hope that it will help men of color, as well as white men of all backgrounds, ages, abilities, and “disabilities” to develop some level of awareness about the devastating effects of sexism and homophobia on women and on the LBGTQ community. More importantly, I am hoping that the content of this book will encourage many men to make an effort to unmask and challenge their maleness and start fighting alongside women against the patriarchal system that has kept women, especially poor women, as socioeconomic, political, and sexual hostages. I also hope that this book would stir up the human consciousness of many whites about the devastating effects of institutionalized racism and white supremacy on people of color, and that they will take action against this form of racism. I want to end this foreword with a poem that I wrote while I was working on the manuscript of this book. It is called They Say and its content captures some of the issues that this book addresses.

They Say

They say that they can break me,

Because they were the ones who made me.

They say that it is time that I finally realize

That my black ancestors were not civilized

That they were uneducated, stupid, and savage

Like untamed animals that are put in their cage.

They say that I am physically strong because I am black,

So it is ok if they stand on and break my back.

Sometimes, they look at my skin and call me brown,

And they say it’s ok if I want to stick around.

They say that my hair is kinky, nappy,

So I can get angry and be unhappy.

They have portrayed me in the media as violent, as lazy.

When I make my voice heard, they say that I am crazy.

Recently they see me walking in the school hallway.

Without thinking, they arrogantly call me and say:

Are you the new housekeeper, the new Janitor?

I look at them and say: No. I am the new professor.

They say that my nose is too big, too flat, and looks too African.

To mimic them, they say I must have one that looks European.

They say that I eat too much and that I am too fat.

So to look attractive and sexy, my belly has to be flat.

They say that I have AIDS because I am promiscuous and reckless

They also say that it is my fault to be HIV positive because I am careless

With regard to my identity, they try to construct and censure everything:

My gender, sexuality, and blackness. It feels as if I have control over nothing.

They say that I am a rebel for refusing to follow their male-European standard.

As a severe punishment, they say that I will always be under their radar.

They stubbornly refuse to challenge their heterosexual, white, and male privilege.

And they deny their homophobic, racist, and sexist views, regardless of their age

As I was walking on the street, they looked at me and said: what sexy and fresh meat!

Their friends laughed, laughed, and laughed, and they said that’s cool, that’s very neat.

The next day they saw me; they looked at me and said to their friends: she is so exotic.

I ignored them, but they kept staring at me and said: she must be very romantic.

In their brown, black, or blue eyes, I am nothing but a sexual object,

Which they feel they can use, abuse, and, when they wish, reject.

They blame me for my own misery, poverty, and victimization

As if it I was the one who created my inhuman and dark situation.

They put me in jail unjustly, make me work hard, and wrongly take away my breath

So that I won’t be a threat to them and be there for my family on this earth.

They say that my culture is barbarous and inferior.

But they portray theirs as advanced and superior.

When I speak up against racial, sexual, and social inequality,

They say that I am losing my cool, my mind, and my sanity.

And when I stand up for those who are marginalized and hungry,

They look at me and say: why are you so angry?

In their textbooks, they lie about my African roots, my history,

Which they have put under siege for more than a century.

They have used all kind of tactics, tricks to belittle my humanity,

Which has been oppressed by their male and racial violence and cruelty.

Then they say that I commit too much crime, that I am too violent.

But they do not mind enjoying my music and exploiting my talent.

They can’t stand my blackness, so they say: go back to Africa, to your dry land,

Instead of distributing all the resources they have stolen and kept in their right hand.

I fight back saying: my African land was colonized and has been brutally exploited.

It’s still a poor land that you imperialist, neo-colonizers have still manipulated.

They look down on my cultural heritage criticizing how I behave and dress.

When I dare call them on their prejudice, they look at me as if I was a mess.

They say: why are they so poor? Why can’t they go to a good school and get a job?

And they rush to make this conclusion: they don’t want to work; they just like to rob.

I respond asking them: Why do you monopolize all the resources? Why are you so racist?

They say, “what?” And I say: Perhaps they would not be so poor if racism did not exist.

Introduction

Traditionally, studies on gender have focused on the socially constructed binary between men and women. While showing how women have suffered from sexism, they have failed to examine in depth how men have also suffered from it. Specifically, these studies have not explored the inner struggle of men of African descent with their own maleness, that is, the influence that maleness has had on their identity and subjectivity. Nor have these studies clearly demonstrated to what tremendous degree maleness has influenced various roles men of African descent feel they must play so they can “feel like a man.” “Feeling like a man” is often due to their socially and historically ascribed gender roles in the community of color and in society as a whole.

Over the past decade or so, other studies on gender have emerged and looked at maleness from multiple perspectives offering alternative ways to examine man as a psychological, sociological, cultural, and historical being. This paradigmatic shift has exerted a great influence on the field. However, despite this shift there have not been many case studies like the ones presented in this book, which focus on a considerable number of men of African descent exploring in depth the disastrous psychological, social, and cognitive effects of maleness on them, their family, and their community.

Drawing on thought-provoking and heartfelt stories of fifty men of African descent who vary in age, social class, family status, sexual orientation, ethnicity, nationality, and ability, this book aims to cast light on the traditional concerns pertaining to the gender issue, particularly to the maleness issue. It goes on to situate maleness in a sociocultural, historical, and postcolonial context to provide innovative ways to better understand the profound effects of maleness on men of color. By doing so, this book hopes to help students and scholars in various fields develop critical awareness about maleness while simultaneously challenging them to redefine roles assigned to men. Although this book focuses primarily on maleness among men of African descent, it addresses issues that concern men of different races/ethnicities.

The Agony of Masculinity: Race, Gender, and Education in the “New” Age of Racism and Patriarchy takes on the intersection between gender, race, sexuality, and social class to push further the issue of maleness. By doing so, it aims to attract novice students and general readers to the field of gender and racial/ethnic studies while challenging established scholars in women studies and black studies alike to consider novel ways of viewing and representing these fields. Specifically designed for a broad range of readers and scholars from many disciplines, this book aims to open up dialogic spaces for discussions about maleness, sexuality, blackness, whiteness, and institutionalized racism from diverse perspectives. This book explores multiple ways that maleness and blackness have been constructed and interrogates many assumptions on which they are grounded. Furthermore, it critically engages the various sub-disciplines that come under the umbrella of masculinity. While some chapters focus on the sociocultural and historical constructions of black masculinity, other chapters analyze the consequences of such constructions. Specifically, some chapters of the book unravel assumptions and stereotypes about men of African descent stemming from sociohistorical construction of their manhood while other chapters talk about the way they have been misrepresented and treated as a result of these stereotypes and assumptions.

Drawing on personal narratives of the fifty men that uncover the myths embedded in their maleness, subsequent chapters of the book propose alternative ways to help men of color and other men transcend their maleness. Insofar as men, particularly men of African descent, are concerned, this book analyzes all the factors mentioned above to propose the establishment of a dialogical relationship between self-to-self, self-to-community, and self-to-the world. In doing so, this book hopes to help readers understand and transcend the artificial border or bridge that has long been established between the self and the society. The overarching argument made throughout this book is that, like the self, maleness is intrinsically informed by and is in constant social negotiation with the outside world. In other words, it is far from being complete, as it continues to be shaped by sociocultural, political, and historical forces. I argue that asymmetrical power relations among diverse groups of people in society usually inform these forces.

Using maleness as the departure point, I critically analyze the unequal power relations between men and women of color. To help me unravel these unequal power relations and their impact on subordinate subjects, I mainly draw on critical pedagogy and positioning theoretical frameworks. In fact, these two perspectives are central to this book, as they enabled me to deconstruct the informants’ view and position about women’s role in society and examine their experience with institutionalized racism.

In addition to carefully describing and addressing the various concerns pertaining to maleness, critical discussion and analysis of interconnected issues such as racism, sexism, classism, and homophobia run throughout the book. Given the tangible way the multiple dimensions of maleness are analyzed and presented throughout various chapters, readers will acquire a far more sophisticated knowledge of maleness, blackness, sexism, racism, and white supremacy. The book presents to readers a complex but clear set of ideas around these issues.

This book is written in an accessible language with clear definitions of unfamiliar terms provided for the novice reader. I believe that the topics that this book addresses matter deeply to people across gender and racial lines and shape the way we define ourselves and read the world around us. Given its interdisciplinary dimension, readers interested in gender studies, race/ethnic studies, postcolonial studies, social psychology, education, history, sociology, and other areas will find this book germane to their needs.

In the sections that follow, I briefly explain the reasons that led me to use a case study approach for this book. I then delineate the theoretical framework informing this study and describe the methodology used. Finally, I summarize the content of each chapter of the book.

Why the Case Study Approach?

Case studies, which are situated within the framework of qualitative research, may help researchers gain an in-depth understanding of informants involving in a study. Looking at case studies through a similar lens, Nieto (2004) maintains that, “Cases studies can help us look at specific examples so that solutions for more general situations can be hypothesized and developed” (p. 6). Case studies also entail collecting data through participant observation and keeping a record. This “includes taking field notes, taking photographs, making maps, and using any other means to record your observations” (Spradley, 1980, p. 33). Building on Nieto’s and Patton’s ideas, I argue that case studies allow researchers to look at an issue closer and at a deeper level, and afford them the possibility to establish a humanizing rapport with informants. This rapport would help researchers get a better sense of the informants’ lived experiences. For example, as I was interviewing the fifty men involved in this study, they shared with me the way they were socialized to perform their maleness. They also talked about their experience with racism and white supremacy. This information can only be obtained through genuine dialog, and this kind of dialog is possible when researchers and informants have a good rapport.

Through dialog, the informants shared their own definition of “being a man.” The information that they provided about what “being a man” means to them can be used to help us better understand the root causes of their male behavior and performance. Likewise, their narrative about the way they have been discriminated against in society because of their racial background can serve as educational, ideological, and political tools to unveil the deep psychological, social, and economic effects of “new racism” (Bonilla-Silva, 2005). Bonilla-Silva (2005) argues, “Today a new racism has emerged that is more sophisticated and subtle than Jim Crow and yet is as effective as the old in maintaining the (contemporary) racial status quo” (Bonilla-Silva as cited in Leonardo, 2005, p. 18). The concept of new racism that Bonilla-Silva has explored through his scholarly work is central to this book, for it captures the subtle and overt brutal form of racism that men interviewed for this study have experienced here in the U.S.

While analyzing the data collected for this study, I found it hard not to incorporate in my analysis pertinent issues such as racism, blackness, whiteness, and white supremacy. In fact, besides sexism, patriarchy, and homophobia, these issues turned out to be the recurrent themes shaping the content of this study. The echoing voice of these men of color about their experience with racism and white supremacy ran throughout the interviews that I conducted with them. Consequently, their personal narratives inevitably led me to take an unforeseeable direction that I did not initially plan to take: I ended up talking about and analytically linking black masculinity to institutionalized racism much more than I anticipated. Needless to say, the informants’ experience with institutionalized racism fundamentally shaped the content of this book. In what follows, I talk about the conceptual framework that informs this study.

Theoretical Framework

This study is informed by critical pedagogy (Freire, 1970; Giroux, 2003; McLaren, 1999; Kincheloe, 2008; Kincheloe & Steinberg, 1997; Macedo et al., 2003) and positioning theoretical frameworks (Harré & Van Langenhove, 1999; Davies & Harré, 1990; Goffman, 1959). I particularly draw on Paulo Freire’s definition of dialog to frame this study. Through his scholarly work, Freire emphasized the vital role that dialog plays in knowledge construction and relation building among individuals. By engaging in a genuine dialog, I was able to create social and human space with informants involved in this study where we discussed issues revolving around maleness, racism, and white supremacy. By interacting with them, I was able to not only find out their position on these issues but also examine such a position.

Similar to the central argument that sociocultural theorists (Vygotsky, 1985; Bakhtin, 1986) have made about the co-construction of knowledge, critical pedagogy theorists (Freire, 1970; Giroux, 2003; Kincheloe, 2008; Kincheloe & Steinberg, 1997; Rossato et al. 2006) maintain that knowledge is dialectically constructed between people engaged in dialog. However, they challenge us to be mindful of the fact that knowledge is not neutral and that it is politically and ideologically loaded. They also warn us that knowledge is not the private property of an individual who merely pours his/her knowledge in the empty mind of those who are expected to be simply taught (Freire, 1970). Rather, knowledge is co-constructed with others through a genuine dialog. Critical pedagogy theorists urge us to interrogate what knowledge is privileged over others.

In the view of critical pedagogy theorists such as Freire (1970); Giroux (2003); McLaren (1999); Kincheloe (2008); Kincheloe & Steinberg (1997); Macedo et al. (2003), through dialog people not only co-construct knowledge but also develop awareness about social issues that concern them, and such awareness can help people better understand the root causes of socioeconomic and political problems that they face in their daily lives. Such an understanding, in Freire’s account, would in turn empower them to take action against oppressive practices that silence their voices.

Within the framework of critical pedagogy, the agency of individuals is acknowledged, and they are treated as subjects as opposed to objects in knowledge construction. Further, within this framework, individuals are encouraged to use the knowledge they acquire through reading to make sense of the world. As Freire argued (1970), “Reading is not exhausted merely by decoding the written word or written language, but rather anticipated by and extending into knowledge of the world” (p. 34). Freire (1970) went on to emphasize, “Reading the word precedes reading the world, and the subsequent reading of the word dispenses with continually reading the world. Language and reality are dynamically intertwined” (p. 36).

Critical pedagogy theorists also address the ideological component of language (Macedo et al., 2003; Macedo, 1994). An important argument critical pedagogy theorists have made regarding language is that it is not neutral; that is, language is ideologically and politically loaded. They challenge people to unpack the ideological and political component of language. Using critical pedagogy as my critical lens, I interrogated the language that informants in this study used to talk about women and the LBGTQ community. By doing so, I was able to challenge and deconstruct sexism and homophobia embedded in their language by pointing out sexist and homophobic words and sentences, such as homosexuality is not normal, or women are soft and too emotional, that they used to refer to women and gay men. I was also able to challenge them to confront their sexism and homophobia by encouraging them to critically reflect on the statements and assumptions they made about women and LBGTQ people. Moreover, through dialog I challenged all men of African descent involved in this study to examine the possible root causes of their homophobia and sexism. Their position on these issues varied, as they did not have the same experience with and exposure to homophobic and sexist discourses growing up. Finally, through dialog they were able to narrate their painful experiences with individual and institutionalized racism in the U.S.

Positioning Theory

As mentioned earlier, positioning theory, which is grounded in poststructuralist epistemologies, also informs this study. Positioning theory is chiefly concerned with the ongoing and shifting positions of subjects through social interaction. According to Harré and Van Langenhove (1999), “Positioning is a discursive process whereby people are located in conversations as observably and subjectively coherent participants in jointly produced storylines.” (p. 36) The concept positioning has been used in several fields. Within the social sciences field, it was first introduced by Hollway (1989) to analyze the subjective construction and positioning of men and women through discursive practices. Later Harré and Van Langenhove (1999) have used the concept positioning to explain how people take up different positions and are positioned through conversations. Positioning is not static; it is fluid, changing, and takes different forms depending on the context. Through social interaction, people negotiate and take on new positions while refuting the positions others attempt to impose on them. People can position themselves and/or others as “powerless or powerful, confident or apologetic, dominant or submissive, definitive or tentative, authorized or unauthorized” (Harré & Van Langenhove, 1999, p. 33). For example, many men involved in this study position themselves as strong and fearless and position women as weak and fearful.

Given the fluid nature of positioning, one can play multiple positioning roles through social interaction. There are different kinds of positioning. They range from moral, personal, self, other, tacit, and intentional positioning to deliberate self-positioning, forced self-positioning, deliberate positioning of others, and forced positioning of others (Harré & Van Langenhove, 1999; Davies & Harré, 1990). For the purpose of this study, I focus on self-positioning and institutional positioning, as I was interested in finding out about the position of men about sexism, heterosexism, and racism. I also drew on this theory for I was seeking to examine to what degree institutions such as family, church, and schools inform their varying positions.

Self-positioning is the position one takes in a given situation. People position themselves to defend a position, a point of view, or express a sense of agency, i.e., to take a course of action that differs from that of others. Their position varies depending on the sociopolitical, cultural, and social contexts. Self-positioning is linked to institutional positioning. In the case of the latter, the course of action is initially taken by someone else rather than by the individual involved.

Harré and Van Langenhove (1999) argue that “institutions are interested in positioning persons in two cases: when the institution has the ‘official’ power to make moral judgments about people external to the institution, and when decisions about people inside the institution have to be made” (p. 26). In the first case of institutional positioning, the “institution has the moral power to make moral judgments about persons and about their behavior, it will ask people to account for what they are doing or not doing” (Ibid). And in the second case, the “institution classifies persons who are expected to function within that institution, performing a certain range of tasks in coordination with the task load of others” (p. 27). Harré’s and Van Langenhove’s (1999) statement illuminates the institutional pressure deriving from family and the Bible by which many of my informants seem to abide. This institutional pressure informs how they view and consequently position women. While some position women as weak and soft, others position them as too emotional. Finally, through their narrative the informants in this study express how they felt about being stereotypically positioned in this society because of their racial background and how they have resisted the misrepresentation of their identity through institutional positioning.

Methodology

I started soliciting participants for this study in February 2008 after I finished crafting ideas about what should be the main focus of this case study. I made a list of about 60 men who I thought would be willing to participate in the study. Only fifty of them agreed to take part in it. I emailed potential participants, including university professors, graduate and undergraduate students, and blue-collar workers, inviting them to take part in the study. Furthermore, I designed a questionnaire that contained queries about blackness, masculinity, and maleness. In addition, I wrote a consent form soliciting the permission of participants to publish what they shared with me in the interviews and questionnaires and assuring them that their identity will be protected.

For example, I sent the consent form along with the questionnaire to an African professor who I thought would be willing to participate in the study. I was hoping that I would get some insights from him about the way he understands and performs his maleness as well as how he has coped with racism in this country. The African university assistant professor replied to my invitation saying, “Hi Pierre, I looked at the questions, but I just don’t connect with the questionnaire. I think I will pass on this one. Sorry about that! Maybe the next study.” The invitation letter that I sent to everyone including this African professor reads as follows:

Dear …

I hope this email finds you well. I am working on a book project that focuses on the deconstruction of maleness/masculinity among men of African descent. Toward this end, I need to interview about 60 men of African descent (i.e., Africans, African Americans, Caribbean and Afro-Latino men) of various ages, social classes, and sexual orientations. Hence, I am writing this letter to humbly ask you if you would be willing to give me 20–30 minutes of your time so I can ask you a few questions either through an interview or a questionnaire. I also need your permission to quote and use whatever you say in the questionnaire or in the interview in the book.

Your real name will not be used in the book; I will use a pseudonym for each participant. I believe this research will contribute to a better understanding of the impact of maleness/masculinity on both men and women of color and on our community of color as a whole. This research will also help us question and redefine the gender roles that have been assigned to us since adolescence. As many of us know, these gender roles have prevented many of us from being in touch with ourselves. Because of the pressure of these roles, many of us have felt that we always have to try to “be a man.” Often when we try to “be a man,” we knowingly or unknowingly do so at the expense of our feelings and others’ well- being.

I have attached here a consent letter and a questionnaire form. If you wish to participate, please sign the consent form and take some time to answer the questions in the questionnaire and send it back to me. Or if you prefer to be interviewed, please let me know. In fact, I would prefer have a face-to-face conversation with you. Thanks in advance for your time.

The questions that I designed both for the interview and the questionnaire were the following:

- Please say a little bit about yourself. For example, your full name, and, if you do not mind, you can say how you identify yourself sexually, what is your status (single, married, divorced, widowed), your profession, your age, and what social class (working class, middle class, or upper class) you feel you belong to.

- What does the expression “be a man” mean to you?

- Has there been any time in your life when you felt it is tough to be a man and/or you felt that you could not do what is expected of you as a man? How did you feel living this moment? What did you do to cope with it?

- In your family, your community, and in society as a whole, what are some of the things that are expected of you to accomplish in order to be seen and treated as a man? What has been your attitude toward these things they want you to do because you’re a man?

- Has it been difficult or relatively easy for you to be a man in this society? If so, why? If not, why not?

- Do you think a homosexual man is less than a man because of his sexual orientation? What is your opinion about the level of homophobia in the black (African American, Caribbean, and African communities) community?

- How would you link black masculinity to the legacy of colonialism?

- Do you think such a legacy influences how men of African descent behave?

- How about institutionalized racism? How do you think it shapes the masculinity/maleness of men of African descent?

- Is there anything you wish to share about your experience as a man of African descent in the U.S and other countries?

Though disappointed that the African professor said that he could not relate to these questions, I accepted and respected his decision not to take part in the study. Unlike him, other men of African descent verbally agreed to take part in it. However, many of them backed out when I decided to set up a time to interview them. Others asked me to email them the questionnaire but never answered the questions listed in it; in fact, many of them did not even acknowledge the reception of my email, let alone respond to the questions formulated in the questionnaire. Fortunately, the majority of invited informants responded positively to my invitation and were eager to take part in this study.

Teenagers, young adults, and senior citizens were among the men who willingly and happily participated in this study. They belonged to diverse backgrounds in terms of their social class, abilities, “disabilities,” geographical locations, cultures, and sexual orientation. Specifically, I interviewed able-bodied men of African descent as well as those with some type of disability. Moreover, I interviewed men who identified themselves as gay, bisexual, transsexual, straight; who were undergraduate and graduate students; who were university and community college professors; who were not formally educated and doing blue-collar types of jobs; who were high school and college dropouts; who were musicians; who were taxi drivers but had a college degree; who were guidance counselors working with teenage boys and girls; who were advisors; who were coordinators of student services at a community college; who used to buy and sell drugs and were imprisoned for drug trafficking; who owned strip clubs; who spoke multiple languages; who were immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean whose first language is not English; and Haitian men who resided in Haiti. Finally, I interviewed black men who were single, divorced, and married.

Only a few of these men answered the questions that were in the questionnaire; the majority were interviewed. Some answered the questions in the questionnaire and additionally made themselves available to be interviewed later. While I interviewed some at their school, their work place, and social and cultural events, I interviewed others in public parks. With the exception of a few men who were and are still living in Grand Valley, Michigan; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Port-au-Prince, Haiti; and in Boston, Massachusetts, most of the men were and are living in major cities in western Massachusetts such as Amherst, Holyoke, Northampton, and Springfield.

All the interviews were face-to-face, with the exception of two that were done over the phone. Before I began my interview with the participants, I introduced myself and clearly explained to them the purpose of the study. I told them that they should not feel obligated to answer any question that they do not feel comfortable answering. I also asked them for their permission to taperecord the interview. Once I obtained their permission, I then proceeded to ask them to briefly talk about their background.

My set of questions focused primarily on maleness and blackness. In the follow-up questions, I asked them to establish a connection between the two. I also tried to obtain their insights about how they feel the legacy of colonialism, racism, and white supremacy shaped their masculinity. I tried to make the interview as interactive as possible, and I allowed them enough space to talk about their experiences without my interrupting. I interrupted only when I needed to ask for clarification.

Moreover, throughout the interview, I allowed the informants enough space so they could talk about the experience of their family members and friends with sexism and racism and the pressure they received from family members to behave and act like a man. Some of them talked about how their parents, relatives, and friends shaped their male behavior. Others talked about how they expect women, particularly their wives and daughters, to behave. Still others pointed out the expectations they set for their sons.

I interviewed each participant for about an hour, although some interviews lasted for over an hour. I used a digital tape recorder to tape all interviews, which were transcribed for analysis. Because of the time factor, not all of the participants had the opportunity to listen to the interviews after they were conducted. Only a few of them did listen to the recorded interviews, though my goal was to have all the participants listen to them so they could, if they deemed necessary, provide additional information. Those who lived close to where I did allowed me to do a follow-up interview with them. From this category of participants, I was able to ask additional clarification questions that I was not able to ask during the first interviews.

The Case Studies

I carefully went through and did a thematic analysis of all interviews. Some of the themes that emerged from my analysis were: blackness, colonialism, masculinity, white supremacy, and racism. I arranged each chapter by theme. At the end of each chapter, I included case studies that cover similar themes addressed in the chapter. A few case studies whose content provides invaluable insights about various themes are used in more than one chapter while others are not presented at the end of the chapter. For some case studies, I only used excerpts extracted from them in some chapters to illustrate some points and/or my positions about certain issues. These case studies are not presented at the end of a chapter like the other case studies as the informants significantly deviated from the issues that I tried to investigate in the study.

The stories of participants in many of the case studies are presented as they ran through the interviews. While some participants provided detailed information about their private lives, others did not. For each case study, I provided a short biographical note of the informant so that the reader has a sense of the informant’s lived experience with maleness, racism, homophobia, and other pertinent issues that this study addresses. In doing so, my goal was to connect the core of each informant’s story to issues addressed in each chapter.

Interpretation of Informants’ Stories

After I presented the case studies, I briefly commented on them and made some suggestions as to how educators can use the case studies to engage students in class discussions about pertinent issues such as maleness, sexism, racism, homophobia, and white supremacy. While my goal was to interpret as accurately as possible the stories of the participants, I do not intend to claim here that I fully captured the core of their stories. My interpretation of their stories is partial.

The people who are in the best position to deconstruct meanings embedded in their stories are the participants themselves. As a researcher, I felt that it was my responsibility to ground my interpretation and claims based on the evidence drawn from their stories. This explains my decision to present their stories as they were constructed throughout the interviews so that the reader can refer to the texts and seek the evidence for any claim that I may have made about their personal narratives.

To avoid possible distortion of the meaning embedded in their stories, while editing the interviews I only left out most common interjections such as you know, overuse of but statements, and um. I also fixed some run on sentences that I felt might be a bit distracting to the reader. However, I avoided making too many grammatical corrections, as I was concerned this might affect the core meaning of the participants’ stories. Finally, while conducting this study, I made validity and ethics my chief concerns.

The Importance of Validity and Ethics in Qualitative Research

Validity, a key term in qualitative research, has historically been contested, debated, and even redefined. Validity is a fluid term and has been defined and understood differently in many fields of study and research methods. For example, the way validity is defined and understood in ethnographic and anthropologic studies might not be the same way it is defined and understood in disciplines such as Math or Physics. Depending on what approach one takes or the method one uses, validity can be read and understood differently.

Researchers sometimes disagree on what makes a research valid, as they often do not concur on a single definition of the word validity. How do researchers then evaluate the validity of their research if the word validity is debatable and contested? In other words, on what grounds should researchers base their research so they can confidently assert that it is valid, or convince readers that the outcome of their research is not greatly influenced by their biases and their agenda? In order for research to be deemed trustworthy, researchers must provide a detailed and clear explanation of the way the research is conducted. More specifically, researchers ought to delineate how data are collected and analyzed, and to what degree the data reflect the lived experience of informants involved in their research. Therefore, researchers need to demonstrate step by step how they arrive at any conclusion drawn from their data; they also need to base their interpretation of data on concrete evidence, which readers should be able to find in their analysis.

Being aware of and taking into account these important factors while doing this study, I made sure that I provided a “thick description” (Geertz, 1973) of my methodology. Moreover, knowing that generalization about an issue can impact the credibility of a research, I made certain that I pointed out the particularity of this study and acknowledged its limitations. Specifically, I clearly noted that the experience of the informants in this study with racism and maleness does not necessarily reflect the experience of all men of African descent with these issues. Each statement that an informant made about his experience with maleness and blackness is contextual and should be taken as such. As much as possible I provided a description of the background of informants who participated in the study. I did so because I wanted to the reader to be able to picture the characteristics of each informant. Furthermore, to ensure the informants knew about the purpose of the study, I wrote a consent letter detailing what my research was about. Moreover, I informed them about their right to refuse to participate in this study. Finally, I told them that they have the right to refuse to answer any questions that they did not feel comfortable answering.

Another key concept that goes hand and hand with validity is ethics. Like validity, ethics challenges researchers to reflect on their actions/behavior while doing research. Researchers who have a strong sense of ethics make the effort to reflect on their research practices and try not to impose their belief and ideology on their informants and overwhelm them with things related to their personal life. Such researchers also acknowledge the possibility that biases might influence the outcome of their research, so they try to constantly question their biases through self-reflection and reflexivity. Finally, they make sure that the privacy of their informants is protected and not revealed to anyone. In this study, I made sure that I did not manipulate the informants to provide any particular answer to satisfy my biases. Also, I tried not to say anything that could have influenced the answers that they provided through the interviews that I conducted with them. Finally, I tried as much as possible to protect the identity of my informants by not using their real names and revealing the information that they shared about their lives to friends and colleagues.

Outline of Chapters

In the first chapter, I use the Caribbean as a point of departure to explain how women, including female relatives and neighbors, have been victims of the patriarchal system. Drawing on personal and communal experiences, I describe how boys and men in the Caribbean have been socialized to perceive and treat women as subordinate. Moreover, using my schooling experience I talk about how the school curriculum has silenced the voice of some Caribbean women including those who have contributed to world history. I go further to examine the ways in which the normalization of heterosexism in the Caribbean has led to the marginalization of gays and lesbians. Furthermore, I explain how I became aware of sexist and homophobic views that were inculcated in my mind as a boy and how I challenged and rejected those views. Finally, while acknowledging and interrogating my unearned male privileges, I recount how I have been targeted and discriminated against because of my racial background.

The second chapter explores the intersection between black masculinity, slavery/ colonization, institutionalized racism, and social class. Specifically, this chapter illuminates how black masculinity has been colored by these factors and the ways in which men of African descent have been misrepresented in the media, targeted almost everywhere, and marginalized as a result. At the end of the chapter, I use President Obama, Retired General Colin Powell, and Clarence Thomas as prime examples to point out how classism and heterosexism can complicate black masculinity. Finally, I examine to what degree homophobia has led to the marginalization of people of Afro descent who are gays, lesbians, and transgenders.

Chapter 3 takes on the hegemonic discourse of blaming the “other” and shows how this discourse has failed to capture the underlying reasons that have prevented many marginalized men of African descent from providing for and being involved in the lives of their families. This chapter also examines how religious beliefs and cultural norms of some informants have shaped their sexist views about women. The chapter ends with a critical analysis of the manner in which many men of African descent labeled “clean and articulate” have been used by privileged white males to directly and/or indirectly demonize other men of African descent who challenge the status quo.

Chapter 4 analyzes in depth how many forms of oppression (racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, and patriarchy) are interrelated and have negatively impacted women, particularly women of color, men of African descent, and other marginalized groups. After critically examining how these forms of oppression are linked to one another, I make an appeal for inter-gender and racial alliances/relations among people from different races, genders and sexes to collectively fight against these oppressions.

Chapter 5 consists of an open letter to men including privileged heterosexual white males and men of color. In this letter, I first analyze how the patriarchal system has led to the subordination of women and the way in which whiteness has granted whites unearned privileges. I go on to call on men of all races to transcend their maleness and individual whites of all backgrounds to go beyond their whiteness and join the battles against sexism, racism, and white supremacy. Finally, I invite all men of color to use their inner strength and try to transcend the venomous socio-economic milieu that has led many to engage in self-silent physical and psychological death. The afterword provides a critical analysis of the racial and socio-political nature of the controversy in which President Obama, Professor Henry Louis Gates, and Sgt. James Crowley were involved.